Full name: Vladimir Vladimirovich Nabokov

Date of birth:

April 22, 1899

Zodiac sign:

Taurus

Age:

78 years

Place of birth:

St. Petersburg

Date of death:

Died: July 2, 1977

Occupation:

Playwright, poet, translator, literary critic

Height:

187 cm

Education:

Cambridge University

Family status:

Married

Spouse:

Vera Evseevna Nabokova (Slonim) (1902-1991)

Children:

Dmitry Vladimirovich Nabokov (1934-2012)

Childhood and youth, family

Vladimir Nabokov was born in St. Petersburg on April 22, 1899 in a large family with noble roots.

His parents were rich people, so his biography included a happy, carefree childhood. The boy’s father, Vladimir Dmitrievich, won a gold medal after graduating from school, became a lawyer and was a worthy role model for his children. The mother of the future writer, Elena Ivanovna, was the daughter of one of the richest landowners, Rukavishnikov, who owns a gold mine. Volodya remembers a large three-story family home, where the city aristocracy often gathered. The boy had two sisters and two brothers in his family.

I often recalled trips to distant Italy and Sweden. Children in the Nabokov family read and drew, and absorbed the ability to speak several languages from infancy. Volodya played football, loved tennis, rode a bicycle and developed mental alertness through chess. Vladimir knew English perfectly, but also spoke French very well. The boy's alphabet of the Russian language was constantly mixed into one thing, and did not want to separate and exist independently.

Vladimir continued his studies at the school where Osip Mandelstam, Nikolai Stanyukovich and other literary figures once studied. Studying at the Tenishevsky School was beneficial. He learned to polish every word for his works. Readers really liked his stories. Nabokov is still performed on stage and films are made based on his stories.

The writer was not shy and did not flaunt the wealth of his family; he believed that this is how one should live. An expensive car was brought to the young man, and the door was opened in front of him. Vladimir was not amused by this; he was passionate about literature and collecting butterflies. He very often devoted pages of his works to these insects.

This is exactly how Vera Nabokova signed herself when fame had already found Nabokov and he became a living classic before the eyes of his contemporaries. It is impossible to downplay the role of Vera in this transformation. Ogonyok publishes a fragment from a new biography of the writer’s wife, dedicated to the most tragic period of their life together.

Stacy Schiff

This is a story about a woman, a man, and also about a family union... Even ill-wishers admitted that Vera Nabokova takes an unprecedented part in her husband’s work.

The Nabokovs came and went together. As a rule, Nabokov almost never appeared alone in public. The spouses were not only inseparable, their thoughts merged: both on paper and in communication. They also had one diary between them. Both handwritings are present in everyone's notebook; Nabokovsky's notes begin at one end, Verin's - at the other.

Stacy Schiff. Vera (Mrs. Vladimir Nabokov): Biography / Trans. from English O. Kirichenko. - M.: KoLibri, 2010

For the biographer, they were unfavorable material: they were too rarely separated. The Nabokovs' relationship seemed to many to be an amazing story of great love.

From an early age, Vera felt the need to join something great in life. Nabokov, as he claimed after his first meeting with her, became extremely in need of Faith.

Lawyers, publishers, relatives, friends - everyone agreed: “Without her, he would not have achieved anything in life.” This marriage placed Vera in the spotlight; nature commanded her to stay in the shadows.

There was only one person in the world who invariably had a close-up view of her. In her presence, Nabokov behaved in a very special way. He flirted animatedly with his wife; made fun of her. It seemed as if both were hiding some kind of secret from everyone. And in their later years, these two behaved in public like children who, in front of adults, quietly negotiate what should be said out loud and what not.

Nabokov presented himself in a highly embellished form... Nabokov reveled in the fact that Vera idealized him, seeing himself as completely special in her eyes. Having met him for the first time, Vera guessed that this was the greatest writer of his era; She served only this truth for the next 66 years of her life, as if rewarding herself for all the losses and storms, for all the historical cataclysms. She did everything possible to ensure that Nabokov lived not in time, but exclusively in art, and protected from the fate of so many of his characters, who were in the grip of various passions. The writer's talent goes into work, not into everyday life - Vera regularly had to explain this to family members; Nabokov forwarded their letters to his wife, and she wrote replies.

There is an opinion that the Nabokovs “turned their union into a work of art.” Thanks to him, they went through a rich creative path together. This unique relationship spans the Berlin period of the 1920s, their life in the American province of the 1950s, and the Swiss period of the 1960-1970s. After the appearance of Lolita, Vera became Nabokov for the public, became his voice. In many ways, the arrogant, inaccessible, incomprehensible V.N. was her creation. If you try to open this unity, you will see what the monument is based on, what is hidden underneath it.

***

From January 18, 1937, when Vera put her husband on a train to Belgium, and May 22, when they united, Vera received letters from Vladimir every day, sometimes two a day. During these four intense months, Nabokov did everything to advance his career, perhaps to the detriment of his own creativity.

The situation was complicated by the fact that in February Vera began to clearly oppose the idea of moving. “Tell yourself that our life in Berlin is over—and please get ready,” her husband begged, continuing his tireless attempts to prepare the way for the family’s move to France or England. However, Vera began to invent all sorts of annoying excuses for delay. In the following months, the voices of the spouses sound in languid dissonance. He said: March, she insisted on April. He said: France, she said: Belgium. He said: France, she said: Italy. He said: France, she said: Austria. Suddenly, Vera began to be extremely concerned about the fate of Vladimir’s mother, who was promised to show her her grandson, whom she had not yet seen; she insisted that one could not go to the West without first going with the whole family to the East, to Prague.

Finally, Nabokov exploded. How is it possible, after all the efforts he made to get hooked in London or Paris, and go to the outskirts of Europe, to the East, refusing the opportunities that open up?!

On May 8, when the couple were separated, Nabokov was still writing from Paris. He became a helpless victim of bureaucratic machinations. It turned out to be impossible to break through the wall of the Czech consulate with your head to obtain a visa. He asks Vera to make efforts on the Prague side. Under no circumstances should she come to France, otherwise he will never receive the required papers. Vladimir begs Vera to intercede for him; She contemptuously replies that he, apparently, is not at all eager to meet her. Nabokov seems more desperate than ever. He had already begun to forget the features of Vera’s face; he is afraid that Dmitry, when he sees his father, will not recognize him. He begs not to aggravate his torment with constant reminders of the unbearable expectation. Literally at the last minute, after endless visits to consulates and embassies, deeply in debt, with complete chaos in all matters, but with a new book maturing in his head, Nabokov boarded a train heading east on May 20. A couple of days later the family is reunited.

Nabokov found his wife in a terrible mood and completely exhausted. The stay in Prague turned out to be short and sweet and sour. When he said goodbye to his mother that year, he could have assumed that he was doing this for the last time.

At the end of June the family moved to Paris. They briefly visited the World's Fair, which attracted record numbers of tourists to Paris; The huge swastika that crowned the German pavilion designed by Albert Speer spoke much more eloquently about the prospects for life in the country than the bright and multi-colored exhibits. On July 7, the Nabokovs went to Cannes, where they checked into a modest hotel a five-minute walk from the beach.

A week after arriving in Cannes, Vladimir confessed to what Vera had long suspected. He was in the midst of a whirlwind romance. The object of his passion turned out to be Irina Yuryevna Guadanini.

Nabokov was still “in a passionate oblivion.” Unable to fight his passion, he even thought about leaving Vera. Vera claimed that her reaction was simple: “I believed that since he loves, he should be with the woman he loves.” In fact, Verino’s attitude to the situation was not so philosophical, much more in the spirit of the sincere advice that she later gave to one young poetess: “Never give up what you love.” Nabokov wrote to his beloved that Vera was not going to agree to a divorce. At the same time, he couldn’t imagine life without Irina. It was difficult for him to imagine how he would return to his old life; he begged Irina to be patient, just as he had begged Vera a few months earlier. He wrote that the day he confessed to his wife became the darkest day in his life after the murder of his father. And for Vera, it was even more so the darkest day in her life.

Using her father's example, she saw how men leave their wives; emigrant life and the unsettled life of Berlin in the 20s did not at all contribute to the strengthening of marriage ties. All his urgent requests to come to him immediately highlighted one striking detail: Vladimir did not want his wife to end up in the Paris area. Her suspicions were confirmed to the smallest detail in an anonymous four-page letter she received in mid-April, just as the Paris-Prague controversy was intensifying.

The author of the anonymous letter described in detail Vladimir’s infatuation with Irina, “a pretty blonde, as eccentric as he was,” adding that Nabokov had made quite a few enemies for himself in literary circles. Flirting was a natural manifestation of Nabokov's nature. He met Irina Guadanini and her mother, Vera Kokoshkina, in 1936 during his trip to Paris, after which he wrote letters to both at the same time. Madame Kokoshkina was not as fascinated by Vladimir as her daughter. This experienced lady considered Nabokov a brilliant writer, but an unreliable person. Already in February, Vladimir and Irina had a romantic relationship; she adored his poetry and attended his performance in January 1937—he visited her three times the following week. Three years younger than Vera, Irina was a cheerful, extremely emotional blonde young lady, divorced after a brief marriage. She had a melodious laugh, a lively sense of humor and a passion for word games. And this time Nabokov was also seduced by the exceptional memory for his poems. In Paris and its environs, Irina Yuryevna worked part-time caring for dogs. And she had a reputation as an insidious seductress, which was strengthened with the appearance of Nabokov in her life.

When Vladimir spoke about the catastrophic state of affairs in Germany, asserting that “God speaks through the lips of a writer,” tears sparkled in Irina’s eyes. "How beautiful!" - she whispered, freezing. She did not leave his side all evening and appeared next to him too often that spring. As soon as he arrived in London in February, Nabokov immediately called her. She loved the dent his head made on her pillow, the cigarette butt he left in the ashtray. Tears streamed down Vladimir’s cheeks when he confessed to her mother that he absolutely could not live without Irina. The only mundane activity in their relationship was playing hangman, drawn in Irina’s sketchbook.

Vera inevitably had to find out about this affair; it developed without much precaution. Perhaps he would have surprised few people if Vera had not had the reputation of being his closest assistant and Vladimir had not had so many ill-wishers. Few people believed that Nabokov could do without his wife. Blind passion is one thing, but human intimacy and understanding is much more rare.

Mark Slonim, editor of an émigré newspaper in Paris and a distant relative of Vera, noted that few women could, like Vera, endure Nabokov’s selfishly manic attitude towards literature. How many women are capable of subordinating their lives to someone else's obsession? Nabokov hardly forgot this truth, although now it resonated with unbearable torment in him.

He could not live without Irina - he had never experienced such strength of feeling, but at the same time he could not consign to oblivion the completely “cloudless” 14 years of life with Vera. In June, he wrote to Irina that he and Vera knew each other down to the smallest detail. A week later, Nabokov was already enjoying the delightful harmony of his relationship with his mistress. He couldn’t imagine life without her; abandoning her was beyond his strength. And Vladimir could not make a choice for himself in such a situation, especially keeping Dmitry in mind. The tension was so great that at times he seemed to be losing his mind.

The days spent in Czechoslovakia became an example of duality. It was unbearable to pretend to Vera that everything was fine, as before.

Vladimir sends an encouraging letter to Irina and Madame Kokoshkina, who acts as a smoke cover. To write about his feelings, about “incredible, unparalleled” love, he slipped out into the street. He snatched a couple of minutes at the post office, in a stationery store, where he usually visited extremely rarely. He wrote on a park bench in Franzenbad and carried his letter “like a bomb in his jacket pocket until he dropped it into a drawer.”

Meanwhile, in a conversation with Vera, Vladimir again and again denies what is really happening. He is sick of deceiving his wife, especially since she is unwell. Now under one pretext or another, Vera talks about Irina every day. “You always make fun of everyone, but not Irina!” - she reproaches. Nabokov wrote about these questions to Irina, who noted in her diary that Vera was harassing her lover.

Vladimir could not rid himself of the disgusting feeling of lies, of the vulgar banality of the situation. It was necessary to extract phrases from him with pincers, meanwhile, from personal experience he discovered for himself what Emma Bovary would later teach him: adultery is the most banal way to rise above banality. Nabokov could not justify his behavior, could not forgive himself for crossing out all 14 years of a serene life with Vera. A huge distance now separated him from the “radiant truthfulness” established in the 1920s.

Having gone to the Riviera with Vera and Dmitry, Nabokov left Irina a notebook in which she could cross out the days until his return, just as Vera once did. In general, his letters sound melancholy, just like those he wrote to his future wife 14 years ago. Vladimir wrote about the predetermination of their similarity; admired the commonality of their impressions; felt the impeccability of his beloved’s attitude towards him. When Vera extracted a confession from him, this by no means put an end to the love correspondence. Now Nabokov strove for Irina even more than in Czechoslovakia. Nothing shook his passion. He begged Irina to remain faithful to him, although he understood that this was not entirely fair. He craved long letters. He promised that they would be together in early autumn. And to prove this, he left some of his things at her apartment.

Vera saw her guilt in everything that happened. It seemed to her that she neglected attention to her husband due to the fact that she was forced to take care of the child, and also because of the unbearable material conditions of Berlin life. Vladimir wrote to Irina about this, saying that his wife was trying her best to compensate for her inattention to him. “Her smile is killing me!” - he writes in despair. After his confession, Vera hardly mentioned Irina. “I know what she thinks,” Vladimir wrote gloomily, “she persuades herself and me (without words) that you are an obsession.”

Irina’s mother was not at all surprised by this; she just predicted that Vera would “blackmail her husband and not let him go.” Vera had a lot of patience, although the whole story became sheer torture for her. In a letter to Paris, Vladimir writes that the situation is aggravated by the fact that he and Vera have established an even relationship. He is afraid that he is starting to forget Irina.

In August, probably at the moment when Vera discovered that her husband was still corresponding with his beloved - in the first ten days of the month Irina received four letters, a storm broke out at home. According to Vladimir’s descriptions, such things were happening in the family that he was afraid that for him it would end in a madhouse. Vera subsequently vehemently denied that they ever had scandals. She was ready to swear that the scenes about which her husband writes with regret and which Irina and her mother carefully wrote down from his words in their diaries did not happen at all. Vladimir most likely had no need to invent such a thing; he wrote about it to Paris with cruel directness. If he decided to break up with Irina, he could do it without appealing to her compassion; and it was clear that communication was taking place in a raised voice. On the other hand, there is convincing evidence that Vera threatened to take Dmitry away from his father. Still, there was something that turned out to be above natural truthfulness.

The husband behaved unworthily; she could not consider her behavior unworthy. It was precisely the feeling of painful pride that did not allow her to admit that most of that August passed between them in continuous stormy quarrels.

Irina suggested that Vladimir go somewhere together, even to the ends of the world. In his next letter, he stated that it was Vera who forced him to break up with her. From now on he will not write to Irina.

Then she went to Cannes. Arriving there in the morning, she immediately went to the Nabokovs' house and waited to intercept Vladimir when he went to the beach with Dmitry. Vladimir made an appointment with her later that day, in the city garden. As they walked together along the road to the port during the day, Nabokov assured Irina that he loved her, but could not bring himself to slam the door and leave, abandoning everything else. He begged her to be patient, but did not commit himself to any obligations. The next day, heartbroken and on the verge of suicide, Irina left for Italy, convinced that Vera had managed to keep Vladimir with her by cunning. At the end of the next year, Irina once appeared at a public reading by Nabokov in Paris, but since then she has never met him.

However, Irina did not disappear without a trace, as Vladimir (and also Vera) might have hoped. She was never able to fully recover from this affair; Nabokov remained the greatest love in her life. Irina predicted that Nabokov would cheat on his wife again at the first opportunity, and constantly disputed the assertion that his marriage was flawless. Over the next 40 years, she sang about their unhappy love in her poems and all the time, like Vera, she kept many clippings with Nabokov’s poems in her notebook. In the 60s, Irina wrote the scandalously frank story “Tunnel” about her relationship with Nabokov and meetings in Cannes. It very freely quoted from Nabokov's letters of 1937.

For the rest of 1937, Nabokov worked on the third and fifth chapters of The Gift, a work called an ode to fidelity. This story about the artist in his youth reads like a hymn of gratitude to a woman who literally resembles Vera in everything. In June, he tells Irina that he wrote a stupid essay about fidelity.

Vera fought with the one who posed a threat, with a purely real woman of flesh and blood, while Irina had a more difficult competition with a rival who was partly of literary origin.

Literature

The biography of a full-fledged writer began with a collection of 68 poems.

Unfortunately, these poems had an unflattering review from the critic Vladimir Gippius. The guy ignored the teacher’s words that poetry was not for him. During the outbreak of the revolution in 1917, the entire Nabokov family fled to Crimea. The newspaper "Yalta Voice" gave green color to Vladimir's works. The poet does not stand still, he studies the rhythm of Bely’s poems. During the military coup in Russia, many did not accept the unrest and changes that were happening. The Nabokovs went to Berlin. There, Vladimir becomes a student at Cambridge University, then switches to teaching and is engaged in translations of American literature. Nabokov is distinguished by a deep philosophical approach to many important life problems. He is concerned about the topic of love and emigration from Russia. The writer’s main teacher was Ivan Alekseevich Bunin. Many of the writer’s works were published under the pseudonym “Sirin”. He was repeatedly nominated as a Nobel Prize laureate. Whatever country Vladimir was in, in Germany, then France and America, he shared his knowledge of literature with students, holding teaching positions at universities.

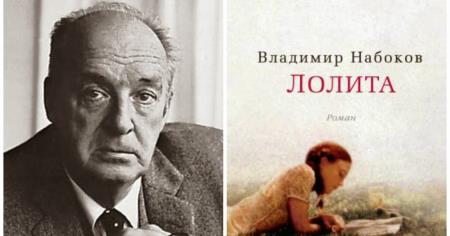

The first to describe the state of mind of his characters was Chekhov. Nabokov also portrayed the characters in detail with play on words and detail, leading them to a completely unexpected outcome of the plot. In this he went much further than the great Anton Pavlovich. The bright, sensational novel “Lolita” was written in French and translated by the writer himself into Russian.

This book contained the forbidden theme of love, the object of which was an adult and a teenager. Later the novel was filmed. Some of Nabokov's thoughts in his works confused even him. This was the reason why the nomination for the award remained a simple nomination for 4 years in a row.

Vladimir Nabokov. Biography and creativity

1922 - Nabokov graduates from Trinity College, Cambridge, where he studies Romance and Slavic languages and literature. In the same year, the Nabokov family moved to Berlin, where his father became editor of the Russian newspaper “The Rudder”. It was in “Rul” that the first translations of French and English poets, Nabokov’s first prose, would appear.

1922-37 – Nabokov lives in Germany. For the first few years he lived in poverty, earning a living by composing chess compositions for newspapers and giving tennis and swimming lessons, and occasionally acting in German films.

1925 - marries V. Slonim, who became his faithful assistant and friend.

1926 – after the publication of the novel “Mashenka” in Berlin (under the pseudonym V. Sirin), Nabokov gains literary fame. Then the following works appear: “The Man from the USSR” (1927), “The Defense of Luzhin” (1929-1930, story), “The Return of Chorba” (1930; collection of stories and poems), “Camera Obscura” (1932-1933, novel) , “Despair” (1934, novel), “Invitation to Execution” (1935-1936), “The Gift” (1937, separate edition - 1952), “The Spy” (1938).

1937 - Nabokov leaves Nazi Germany, fearing for the lives of his wife and son.

1937-40 – lives in France.

1940-1960 – in the USA. At first, after moving to the USA, Nabokov traveled around almost the entire country in search of work. A few years later he began teaching at American universities. Since 1945 - US citizen. Since 1940, he began to write works in English, which he had been fluent in since childhood. The first English-language novel is The True Life of Sebastian Knight. Next, Nabokov wrote the works “Under the Sign of the Illegitimate,” “Conclusive Evidence” (1951; Russian translation “Other Shores,” 1954; memoirs), “Lolita” (1955; he wrote it in both Russian and English), "Pnin" (1957), "Ada" (1969). In addition, he translates into English: “The Tale of Igor’s Campaign”, the novel “Eugene Onegin” by A.S. Pushkin (1964; Nabokov himself considered his translation unsuccessful), the novel by M.Yu. Lermontov “Hero of Our Time”, lyrical poems by Pushkin, Lermontov, Tyutchev.

1955 - the novel “Lolita,” which four American publishers refused to publish, is published in Paris by Olympia Press. In 1962, a film was made based on the novel.

1960-1977 – Nabokov lives in Switzerland. During these years, Nabokov’s works were published in America (books “Poems and Problems” (39 poems in Russian and English, 14 poems in English, 18 chess problems), 1971; “A Russian Beauty and Other Stories” (13 stories, some translated from Russian, and some written in English) (New York). Published by “Strong Opinions” (interviews, criticism, essays, letters), 1973; “Tyrants Destroyed and Other Stories” (14 stories, some of which are translated from Russian, and some are written in English), 1975; “Details of a Sunset and Other Stories” (13 stories translated from Russian), 1976, etc.

On July 2, 1977, Nabokov died in the town of Vevey and was buried in Clarens, near Montreux, Switzerland.

1986 – Nabokov’s first publication appears in the USSR (the novel “The Defense of Luzhin” in the magazines “64” and “Moscow”).

Main works:

Novels: “Mashenka” (1926), “The Defense of Luzhin” (1929-1930), “Camera Obscura” (1932-33), “Despair” (1934), “The Gift” (1937), “Lolita” (1955), "Pnin" (1957), "Ada" (1969), "Look at the Harlequins!" (1974),

The story “Invitation to Execution” (1935 - 36), Collection of stories: “The Return of Chorb” (1930), Book of Memories “Other Shores” (1951), Collection “Spring in Fialta and Other Stories” (1956), Poems, Research “ Nikolai Gogol" (1944), Commentary prose translation of "Eugene Onegin" (vol. 1-3, 1964), Translation into English of "The Tale of Igor's Campaign", "Lectures on Russian Literature" (1981), "Conversations. Memories" (1966)

All inquiries >>

Personal life

In Nabokov's biography, from childhood there were often periods of falling in love. He experienced his strongest feelings at the age of fifteen. An ordinary peasant girl became his object of adoration. The next love arose at the age of 16 for Valentina Shulgina, but their passionate promises did not stand the test of distance. Vladimir moved to Crimea, and with the move, his feelings disappeared.

3 years after this love affair, the writer married a Jewish woman, Vera Slonim. The girl was distinguished by her incredible beauty and ability to be a friend and loving wife to her beloved husband. They read the pages of a new novel together, and caught butterflies together. The couple had an only son. Dmitry inherited his father's ability to master syllables, and he became a translator and opera singer. Among literary scholars there is an opinion that it was Vera who wrote the novels for Nabokov. Whether this is true or not is unknown. But the fact that she edited them is a fact. And Vera also knocked on the doors of publishing houses and raised her connections, just so that her husband’s works would be published.