Name

Researchers do not have a consensus on the origin of the name of the people. Some associate the version of the appearance of the ethnonym with Idar Kabardei, a semi-legendary prince, under whose leadership the people occupied the territories of the Terek basin in the 15th century. According to another version, the prince’s name was Kabarda Tambiev - he is considered the founder of the Kabardian ethnic group. According to legend, the prince moved from the Western to the Northern Caucasus along with one of the branches of the Circassians. Kabardians, like other Circassians, call themselves Adyghe. The ethnonym has ancient roots; researchers could not come to a consensus regarding its appearance. According to one version, the word means “children of the sun.”

Customs and traditions of Kabardians. Birth of a child. Kabardians

By the 21st century, many of them have become outdated and gone out of use by newly made parents and their loved ones, and some, slightly modified, continue to accompany a newborn person from the first days of his life. Among the peoples living in the North Caucasus (Nogais, Adygeis, Abazas, Kabardins, Balkars and Circassians), family rituals are one of the reflections of their national traditions. Thus, they preserve the ethnic specificity of the people of their places.

Where they live, number

During their heyday, the Kabardians occupied vast territories of the Central Ciscaucasia. The region of settlement was named Kabarda, the lands of which were divided into Small and Big Kabarda. There are no exact data on the number of Kabardians before the Caucasian War; rough estimates indicate 35,000 households, which suggests a total number of inhabitants of at least several hundred thousand people. A sharp decline in population occurred at the beginning of the 19th century. The destructive Caucasian War and a severe plague epidemic almost completely devastated Lesser Kabarda and seriously reduced the number of inhabitants of Bolshaya. In 1825, Kabardians were included in Russia. At the end of the Caucasian War, along with other Adyghe peoples, they were forcibly evicted outside the Russian state, mainly to Turkey.

According to the 2010 census, the number of Kabardians in Russia is 517,000 people. Most of them, 490,000 people, live on the territory of Kabardino-Balkaria, making up 57% of the population of the Republic. Number of Kabardians in other regions of Russia:

- Stavropol Territory - 7993 people.

- Moscow - 3698 people.

- North Ossetia - 2802 people.

- Moscow region - 1306 people.

- St. Petersburg - 1181 people.

- Krasnodar region - 1130 people.

Due to deportations, as a result of the Caucasian War and repressions of 1944, a significant part of the ethnic group lives abroad. The largest diaspora of Circassians, including Kabardians, is located in Turkey, according to some sources, considered the third largest people of the state. Circassian diasporas have been recorded in Syria, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Germany, the USA, and North Africa.

Deportation, resettlement and revival

The number of Balkars is approximately 125 thousand people, of which more than 100 thousand live in the republic itself. Representatives of this people survived in the countries of the former Ottoman Empire, where in the 19th century their Muhajir ancestors moved from the now Russian Caucasus. They also exist in Central Asia, where these people were deported in 1944.

The deportation of the Balkars is a black page in the history of the people; how many of them died along the way and in the first months of life in a new place is still unknown. Only in 1957 were they allowed to return to their homeland, with the condition that they not lay claim to their former homes and property.

The Kabardians were against their return, and there is still tension in relations with the Balkars, causing conflict situations. In 1991, the USSR government recognized the deportation as an act of genocide. In 1993, a national flag with a double head in the center was approved. Every year on March 28th the Day of the Revival of the Balkars is celebrated.

What future does this people have? The resettlement of Balkars to their homeland is almost complete, they live on their own land, have the opportunity to preserve traditions and customs, and teach their children their native language. Young people can get any profession and work in any field. Their culture, like that of other small peoples of Russia, is part of the common cultural heritage that needs to be preserved and developed.

The art of cooking is a universal heritage. The national cuisine of Kabardians and Balkars has developed historically and has its own specific characteristics. In general, all food was divided into everyday food - everyday, holiday, travel and ritual. The daily food of most peasants was monotonous. It consisted of ayran, Kalmyk tea, sheep cheese and chureks. Festive occasions and the performance of various rituals were distinguished by large feasts, for which a variety of foods and drinks were prepared.

Kabardians and Balkars solemnly celebrated the birth of a child, especially a boy, who would continue the family line. These celebrations were organized by his grandparents or uncles and aunts. They informed all relatives about the day of the holiday. The family began to prepare the national drink - buza (makhasyma, boza), fried lakums, slaughtered chickens, rams, etc. They prepared national halva (khyelyue). There was no specific date for these holidays. It could have been held in the first days after the birth of a child, or timed to coincide with the ritual of tying a child into a cradle. Relatives brought to the holiday: a basket of delicacies, live and slaughtered chickens, and a live ram.

The most important part of this holiday was the sacrifice in honor of God. The person who was trusted to slaughter a ram or a bull said special words: so that God would make the boy strong, strong, prolong his life, etc. On the day of such a holiday, a competition was held. A post with a crossbar was dug into the yard. Round smoked cheese was hung on the crossbar. The competitors had to reach the cheese along a well-oiled leather rope and take a bite. A prize awaited the winner.

As soon as the child began to walk, a ceremony of the first step (lieteuve) was held, to which neighbors and relatives were invited. To perform this ritual, the child’s family baked special bread from millet or corn flour, which was called “leateuve mezhadzhe” - “bread of the first step.” Those invited brought lakums, chicken, etc. National halva was prepared.

Women and children took part in the ceremony. According to custom, various things were placed on top of the mezhaje: a whip, a dagger, the Koran, blacksmithing and jewelry tools. The child was allowed to choose from them what he liked. If he chose a whip, then he was predicted that he would become a dashing rider; if he chose the Koran, he would become a mullah; if he chose a tool, he would become a blacksmith or jeweler. Such testing of the child’s future inclinations and interests was also carried out for girls.

The Balkars, for example, celebrated the appearance of a child’s first tooth with a special treat to which women and children were invited. For this, various dishes were prepared, but always “zhyrna”. It consisted of well-boiled grains of corn, barley, beans, and wheat, pounded in a special mortar.

Food occupied a large place in wedding rituals. Usually a family whose son got married prepared a large amount of the national drink - buza. They were sure to treat everyone who came to congratulate them. For the wedding day, the family and other relatives prepared various national dishes and drinks. Halva, buza, and slaughtered ram were considered mandatory for wedding celebrations. Usually, before leaving for the bride, all residents of the village were invited to a gathering evening feast. Usually the procession taking the bride away was not released from the yard until the “barrage guard” received a reward in the form of a bowl of buza and various dishes. The wedding procession was accompanied by the aul youth, the bride's relatives, who took with them a jug of buza, lakum, meat, cheese, etc., and a farewell feast was held on the border of the village. On the way, the wedding procession was met by the groom's relatives with drinks and food and organized refreshments in the field, toasts were made, dancing was held and everyone went home together. After the Lezginka was performed in the courtyard, all participants in the wedding procession were taken to their rooms and treated until the morning. The dashing riders who managed to enter the bride’s room on horseback were presented with a large bowl of buza, a plate of pasta, meat, and delicacies.

An obligatory part of the wedding is smearing the bride's lips with honey and butter. This ritual was performed two or three days after the bride was brought on the day of her entry into the large room where the mother-in-law lives. Usually this procedure is performed by the most authoritative woman of the family, and this symbolizes the desire of the family for their young daughter-in-law to be sweet and pleasant, like honey and butter, and for the new family to seem just as sweet and pleasant to her.

According to custom, the groom stayed with one of his comrades on the wedding days. He was visited by friends, relatives, and fellow villagers, who were always given food and drink.

The groom's family was preparing for his return home. They gathered the oldest members of the clan and neighbors. The groom and his companions were waiting at the door of the room where the old people were sitting. The eldest of them, turning to the groom, said: they welcome the arrival of a new person into their family, forgive him for his actions, hope for courtesy, diligence, diligent work, etc. As a sign of “reconciliation,” he was presented with a large bowl of buza with a plate of various dishes, which the groom passed on to his comrades.

Among the Balkars, the groom hid for 7 days, and if circumstances did not allow him to hide for more than 7 days, then a ransom day was appointed. The herald announced throughout the village about the groom’s desire to pay off and invited everyone to the gathering place. Beer and several whole roasted lambs were brought here from the groom, and the feast began. The newlywed was also present at this feast. This ritual ended the entire wedding process. This ritual of the Balkars differed from the Kabardian one. If among the Kabardians the “conciliatory” feast was organized by the groom’s parents, then among the Balkars it was the groom himself. In order to “reconcile” the groom with his mother, the Kabardians held a women’s holiday, where the mother presented her son with a bowl of buza and sat him on a bench. This ritual symbolized the final “reconciliation” of the son with his family.

According to custom, Kabardians and Balkars, when visiting a sick person, brought food. This is still considered mandatory if you come to visit. The usual ingredients for this are boiled chicken, a few rolls, fruits, vegetables, etc. This is also done if the patient is in the hospital. If a man comes to visit, he doesn’t bring anything with him.

Kabardians and Balkars paid great attention to treating familiar and unfamiliar guests. The traveler could count on the most cordial welcome in the home of every mountaineer. Any person was obliged to provide the guest with a hearty table and a good fire. The guest was treated to delicious and varied food. They prepared for the guest: gedlibzhe, litsiklibzhe, delicacies, pies, etc. They were treated to buza, and in Balkaria - beer. But not everyone was treated equally. For example, female guests were treated without the national drink, but sweet tea was always served, which was not given when treating men. National halva was not prepared for random guests, but it was mandatory when receiving guests whose arrival was known in advance. For fellow village guests, if they were not specially invited to the celebration, there was no obligatory guest meal; they were limited to chicken or fried meat.

Kabardians and Balkars are still famous for their hospitality and hospitality. They still observe all the positive traditions and customs associated with the ancient institution of hospitality.

There were also forbidden foods. For example, the girls were not fed chicken stomach; they were told that their lips would be blue. Children were not given kidneys because they “slowed down” growth. Children were also not allowed to eat their tongue, as there was a belief that if a child eats his tongue, he will become talkative.

A lamb was slaughtered for the guests. The most honorable part was the head, half of which was given to the man. Women were not allowed to eat the head.

Numerous traditions and customs developed over centuries were associated with food, its preparation, and serving.

Kabardians and Balkars taught their children the ability to cook food. From an early age, girls were taught to help their mother clean the room, wash and organize kitchen utensils, help in preparing food, and cook it themselves. The mandatory code for raising girls included knowledge of all national dishes, methods of preparing them, and the order in which they were served. A girl was judged not only by her appearance, but also by her upbringing, ability to do needlework, and cook delicious food. Boys were also taught how to cook food.

Kabardians and Balkars have always been distinguished by moderation in food. It was considered completely unacceptable and indecent to say that you were hungry. Greed for food was considered a serious human vice. The custom demanded that he leave some of the food, although he himself was not full. Custom also did not allow one to be picky about food, to choose or ask for one dish and refuse another.

The food was prepared by the eldest woman of the family or one of the daughters-in-law. She divided it among family members.

Usually food was prepared with a certain reserve, because guests could arrive unexpectedly. Moreover, even a well-fed person did not have the right, without violating custom, to refuse food. Being hospitable, Kabardians and Balkars did not take kindly to a guest’s refusal to eat. This could offend them. On the other hand, they looked at the person who ate their bread and salt as their own, dear, close person and provided him with all kinds of help.

In the past, the food of Kabardians and Balkars was characterized by seasonality. In the summer they ate mainly dairy and vegetable foods, and in the fall and winter – meat.

Balkars are a Turkic people living in the North Caucasus, mainly in Kabardino-Balkaria. The number of Balkars, according to official data, is 170,000 people. Religion – Sunni Islam. They speak the Karachay-Balkar language, which belongs to the Polovtsian-Kypchak group of the Turkic language family.

In traditional Balkar society, rituals, ritual games and entertainment were a kind of holiday and theatrical performance, adding a unique flavor to the harsh life of the highlander.

Balkar holidays and rituals, timed to coincide with the change of seasons, clearly represented traditional culture, and their organization showed the creativity of the participants. The symbolism developed over centuries added solemnity and color to the festive event.

In the labor processes of the Balkars, the gaming moment, dating back to ancient folk traditions, was also of very great importance, revealing magical functions - the ritual participants sang songs and performed ritual dances in honor of the supreme deity Teyri, as well as in honor of the deities of fertility, thunderstorms, lightning and thunder - Choppa, Eliya, Shibli.

In the pantheon of agrarian deities of the Balkars, Hardar, who bore the epithet “golden,” occupied a prominent place. In Chegem, the agricultural ritual “Gutan” was carried out widely and magnificently, with the sacrifice of a bull. It is characteristic that the cult of the bull is widespread in the Caucasus everywhere - on both sides of the Main Caucasian ridge - among Georgians (Svans), Abkhazians, Ossetians, etc. The holiday of the first go to plowing was called “Saban-toy”. It was attended by groups of individual householders (saban zhyiyn) or residents of the entire village. For the sacrifice on this occasion, the animal that was born first (tel bash) in a flock of sheep during the previous lambing was fattened. The origins of beliefs and rituals associated with agriculture go back to the spiritual world of the early agricultural and pastoral cultures of the Central Caucasus.

A holiday known to all residents of Balkaria, which also attracted representatives from Karachay and Digoria, was the “Gollu” holiday, timed to coincide with the spring equinox. In addition to it, every family celebrated the day of the spring equinox with the preparation of a special dish called ashyr zhyrna, ashyr gezhe.

On the day of the summer solstice, the ritual game “Elek kyz” was performed. The first-born girl (tunguch) from a prosperous family was dressed in a long robe dress. Holding a sieve in her hands outstretched to the sky, she (elek kyz) with a group of her peers walked around the courtyards, all the time rotating the sieve from right to left, eh? the girls sang a ritual song so that the harvest would be rich. This game though? resembles carols (ozai), but most likely it is a fragment of an ancient agrarian ritual.

Haymaking organized and mobilized the community. For the mowers, as well as for the plowmen, a one-year-old lamb, the first to appear in the flock, was slaughtered, and buza and ayran were prepared. During haymaking, the mowers formed a kind of row - usually the most experienced one went ahead, and the rest followed him, achieving maximum synchronization in actions. Thus, young haymaking participants acquired the necessary skills under the guidance of their elders.

An important event was the shearing of sheep, which also began with magical rituals. Women came to the shearers with national pies (khychin), placing them on clean straw. It was forbidden to transfer pies to a dish (yrys). When shearing sheep, it was forbidden to eat fried food...

In the family - the primary unit of society, the most important social institution - the primary socialization of the individual occurs, and the traditions of previous generations are assimilated. Different types of families corresponded to different historical periods. An important stage in the development of the family was a large patriarchal family, consisting of several elementary families and generations, where kinship was counted through the male line.

If before the abolition of serfdom among the Balkars the dominant type was a large paternal family, then by the end of the century fraternal families predominated. The authority of the father in the larger family was stricter and more despotic than that of the eldest among the brothers in the fraternal family. In the latter, the function and importance of the family council increased significantly. The authority of the father - the head of the family (yuy tamata) and the mother - his wife (yuy biyche) in traditional families was held high. Unquestioning obedience to them was the law for all family members.

By adolescence, the boy and girl were prepared for going out into the world, taught the rules of good manners. Marriage was an extremely important moment in the life cycle. These events were accompanied by rituals rich in magical and etiquette attributes.

Each age and sex group was labeled with a specific term and played a role unique to it in the family and society. Relations between age groups were fixed by adat and sharia. The basis of the relationships of all individuals, regardless of age, was care, respect and responsibility and everything that constitutes the moral core of the behavior of all generations - courage, hard work, honesty, nobility, caring attitude towards the surrounding nature.

Among the Balkars, like among many peoples, when solving particularly important matters, priority roles in society and family were assigned to men. At the same time, older women played a significant role in managing the household, and their opinion was taken into account when deciding all important issues in the life of the family. Balkar women were not powerless and occupied a rather prestigious niche in the family, kinship and household hierarchy.

At all times, among the Balkars, the opinion of their elders was authoritative and respected in all life situations? situations. The cult of elders was manifested in everything: the elder was the first to make a toast, took pride of place in the house, at the refectory table; in the opposition “right - left” - necessarily the right (prestigious) side. The honorable place of the elderly in the hierarchy of generations, their veneration by the younger ones, the favorable psychological climate, and spiritual comfort had a beneficial effect on their physical condition. Therefore, in traditional Balkaria there were many long-livers, despite the difficult living conditions in the mountains.

In the system of education of the Balkars, the positive personal qualities of the younger generation were not suppressed, but, on the contrary, were encouraged and developed.

For a Balkar, as for other mountain peoples, a guest (konak) is an important person. He was given a special room (konak yu). This room was furnished with everything necessary for a guest's stay. When implementing the norms of hospitality, the most developed rules of table etiquette of the Balkars are revealed. According to this table etiquette, there was a clear scheme for the use of space and the arrangement of guests and other participants in the meal, a form of greeting and farewell, contact and communication, eating and drinking, etc.

In etiquette, three main factors play a decisive role: gender, age and social status. The basis of the rules of decency were decent behavior (namys), face, conscience (bet), politeness, diligence (adezhlik).

Moral and ethical standards developed in traditional society form the basis of relationships in the modern Balkar family. However, in our age of the exclusive predominance of small families, ancient foundations, customs and rituals are crumbling, the connection between generations is weakening, and the status roles of family members are acquiring a new character.

Urbanization and the infiltrating mass culture affect aesthetics, ethical standards, and national symbols, which act as elements of ethnic identification, are weakening.

In the socionormative culture of any nation, the component of legal culture plays an important role. The result of the centuries-old practice of the Balkar people are adats - unwritten laws that reflect legal consciousness, moral beliefs and ethnic mentality. Adats regulated all aspects of family and community life. They were refined, supplemented, and adapted to new conditions.

The revival of adats and their creative use in modern local lawmaking and conflict resolution is not without a positive perspective.

Balkars are a Turkic people living in Russia. The Balkars call themselves “taulula,” which translates as “highlander.” According to the 2002 Population Census, 108 thousand Balkars live in the Russian Federation. They speak the Karachay-Balkar language. The Balkars as a people were formed mainly from three tribes: Caucasian-speaking tribes, Iranian-speaking Alans and Turkic-speaking tribes (Kuban Bulgarians, Kipchaks). Residents of all Balkar villages had close ties with neighboring peoples: , Svans, . Close contact between the Balkars and the Russians began around the seventeenth century, as evidenced by chronicle sources where the Balkars are called “Balkhar taverns.”

At the very beginning of the 19th century, Balkar societies became part of the Russian Empire. In 1922, the Kabardino-Balkarian Autonomous Region was formed, and in 1936 it was transformed into the Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. In 1944, Balkars were forcibly deported to the regions of Central Asia and. In 1957, the Kabardino-Balkarian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was restored and the Balkars returned to their homeland. In 1991, the Kabardino-Balkarian Republic was proclaimed.

For many years, the Balkars were engaged in cattle breeding, mainly raising sheep, goats, horses, cows and the like. They were also engaged in mountain terrace arable land (barley, wheat, oats). Home crafts and crafts - making felts, felts, cloth, leather and wood processing, salt making. Some villages were engaged in beekeeping, others hunted fur-bearing animals.

Until the nineteenth century, the Balkars professed a religion that was a combination of Orthodoxy, Islam and paganism. Since the end of the seventeenth century, the process of complete transition to Islam began, but it ended only in the nineteenth century. Until this moment, the Balkars believed in magical powers and endowed stones and trees with magical properties. Patron deities were also present.

Traditional home

Balkar settlements are usually large, consisting of several clans. They were located in ledges along the mountain slopes. For defense purposes, unique towers were erected. Sometimes the Balkars settled on the plains, standing their houses in the Russian, “street” manner with estates.

In mountain settlements, the Balkars built their dwellings of stone, one-story, rectangular; in the Baksan and Chegem gorges they also built wooden frame houses with earthen roofs. According to the family charter, which was in force until the end of the 19th century, the sleeping honor of the Balkar house should be divided into two halves: female and male. In addition, there were utility rooms and sometimes a guest room. Houses with 2-3 rooms with a guest room (kunatskaya) appeared among wealthy families at the end of the 19th century. In the 20th century, two-story multi-room houses with wooden floors and ceilings became widespread. In the old days, the Balkar home was heated and lit by an open fireplace.

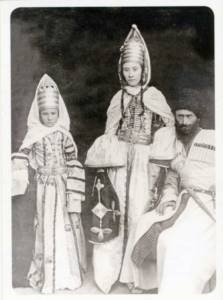

Folk costume

Traditional clothing of the Balkars of the North Caucasian type: for men - an undershirt, trousers, sheepskin shirts, a beshmet, belted with a narrow belt. From winter clothes: fur coats, burkas, hats, hoods, felt hats, leather shoes, felt shoes, morocco shoes, leggings. Women wore shirts, wide trousers, a caftan, a long swing dress, a belt, sheepskin coats, shawls, scarves, and caps. Balkar women pay great attention to jewelry: bracelets, rings, earrings, necklaces, and so on. The festive dress was decorated with galloon, gold or silver embroidery, braid, and patterned braid.

Language

Kabardians speak the Adygebze language, scientists call it the Kabardino-Circassian language as part of the Abkhaz-Adyghe family. Some linguists consider the Adyghe and Kabardino-Circassian languages to be dialects of a single language common to the Adygs. Kabardians agree with the version, as evidenced by the self-name of the language and the possibility of communicating in it with representatives of other Adyghe peoples. Researchers have not found traces of Kabardian writing: legends were passed on from mouth to mouth. If it was necessary to transmit text messages, Arabic graphics were used. In 1885, Umar Bersey compiled the first Circassian primer. Since 1936, the Cyrillic-based alphabet has been used. The native language is taught in the primary classes of local schools. Along with Russian, Kabardino-Circassian is widely used in the everyday life of the people.

Story

The ancestors of the Circassians are the Meotian tribes that occupied the Black Sea and Azov territories in the first millennium BC. Linguistic similarities suggest that the tribes of the ancient Kaskas and Hutts, who inhabited Anatolia and the Southern Black Sea region from the third millennium BC, participated in the formation of the ethnos. The first mention of Kabardians dates back to the 10th century. Constantine Porphyrogenitus described Kasakhia, the country of the Kasogs, located near Alania, Papagia, and Zikhia. By the 16th century, information about the people became more accurate, the area of residence was localized in three directions:

- The foothill and flat territories of the left tributaries of the Terek are a historical area of residence called Kabarda.

- The right bank of the Terek from the mouth of the Sunzha to the mouth of the Kurp is Malaya Kabarda.

- The lower reaches of the Terek, north of Kabarda, which included the territory of Mount Beshtau (Pyatigorsk) - in Russian documents received the name “Land of the Pyatigorsk Cherkassy”, were called Greater Kabarda.

Since the 16th century, strong ties have been established with the Moscow state, due to the goal of influencing a common enemy: the Crimean Khanate. The Kabardian prince Temryuk Idarov (also Idarovich) played a significant role in establishing friendly relations with Moscow. He managed to unite neighboring peoples by drawing up the first embassy in 1552 to Ivan the Terrible. In subsequent years, together with Grozny, the Kabardians took part in the capture of Kazan, Temryuk, Taman, and Astrakhan. The relationship was cemented in 1561 by the marriage of Ivan the Terrible and the daughter of Temryuk Idarov, who after baptism received the name of Tsarina Maria Temryukovna.

After 10 years, Ottoman influence was restored, and a period of feudal fragmentation began in the Kabardian region. Local princes continued to influence neighboring peoples, who adopted the way of life, costume, customs, culture, and rules of conduct of the Kabardians. Noble representatives of the clans entered the Russian service and came to the aid of the Tsar during the Time of Troubles. Prince Cherkassky, as the closest relative of Maria Temryukovna and who was listed first in the Council of the Second Militia in terms of localism, was one of the contenders for the throne. However, the Zemsky Sobor of 1613 settled on a neutral candidate - Mikhail Romanov, whose reign marked the beginning of the 300-year reign of the great Romanov dynasty.

In 1681, Cherkassky agreed on eternal peace with the Ottoman Empire, and in 1739, the Russian Empire abandoned its claims to the territory. Until 1825, when during the Caucasian War the region was re-annexed to Russia, Kabarda existed as an independent state.

Appearance

Anthropologically, Kabardians belong to the so-called Pyatigorsk mix, which is a mixture of Caucasian and Pontic types. Distinctive appearance features include:

- tall or average height;

- athletic build;

- wide face;

- prominent cheekbones;

- straight eyebrows;

- horizontal position of the eyes;

- the nose is straight or with a hump, the tip is horizontal;

- eyes brown, gray, black;

- straight, coarse hair;

- hair is developed.

Researchers of the 16th-19th centuries. noted the attractive appearance of the Kabardians, calling the representatives of the people one of the most beautiful in the Caucasus. The men were distinguished by their athletic build, broad shoulders, agility, and agility. From an early age, boys were taught how to handle weapons and horses, wrestling, and horse riding. Thanks to this, children grew into physically strong, resilient, fit young men. Girls from the age of 12 began to use a corset with wooden inserts in the front. The item of clothing was worn day and night and was supposed to be removed on the wedding night. The use of a corset ensured ideal posture, a slender figure with a thin waist and small breasts: such an appearance was considered the standard in the Caucasus.

How does matchmaking and engagement work?

Kabardians are a rather leisurely people, especially in such an important matter as choosing a bride. It is believed that a young man cannot adequately assess how good a woman will be for him as a wife. Therefore, relatives take a closer look at available girls, drawing conclusions about how well they are brought up.

This is a rather slow method, but it allows you to collect all the information about a potential relative. Thanks to this, even a small stain on the girl’s reputation will be noticed, which will worsen her chances of a good marriage. When a guy expresses a desire to marry a girl, and if the elders of the family have no objections, then matchmakers are sent to the bride’s parents.

Among the delegation there must be an eldest man in the family who talks about his desire to become related. Parents can immediately refuse the groom, or take time to think about the proposal. Sometimes the reflection period reaches 4–5 months. After this, a second meeting takes place, where the decision is announced.

Sometimes the bride’s parents may immediately refuse the groom, but if the man is serious, then he tries to correct as quickly as possible what the girl’s family did not like. After this, matchmakers are sent again, but 3-4 months should pass between visits. When permission is received, the matchmakers and parents thoughtfully discuss the size of the bride price. This may take 1–3 months, depending on the frequency of meetings. It is considered incorrect and too suspicious if an agreement is reached very quickly.

When the conditions are satisfied by both parties, the engagement is considered concluded, after which preparations for the wedding begin.

Cloth

The Kabardian princes were considered the trendsetters of the Caucasus. The traditional costume consisted of trousers, morocco tunics, a high-necked shirt with buttons, a beshmet, a Circassian coat, and a hat. An obligatory element of the costume is a richly decorated inlaid belt or saber girdle for edged weapons: a dagger, a checker, a saber. The Circassian coat of black, brown, red, white color was complemented by gazyrs and a bib. In the cold season and on hikes they wore burqas, and for everyday wear they used sheepskin coats. The women's costume consisted of a tunic-like shirt reaching to the floor, trousers, and a swing dress. The latter could be casual and festive: formal outfits were decorated with gold and silver embroidery, skillfully crafted silver belts, and jewelry made of precious metals. The girls complemented the outfit with a tall hat with gold embroidery. After marriage, it was replaced with a black scarf, the ends of which were wrapped around the neck and tied on the head. An elegant openwork scarf of a light shade was worn on top.

Life

Social organization

Kabardians were divided into five classes or estates:

- Princes. Before the Caucasian War, the top power was made up of princely families; according to some sources, there were six of them. Each clan owned vast territories of Kabarda, had an army, overlords, peasants, servants, and slaves. From among the princes, in different periods, a supreme prince was chosen, who represented the interests of Kabardians outside the historical region of residence.

- Nobles, or uzdeni. Divided into three categories based on birthright and amount of wealth. The first and second are recognized vassals of the prince, noble families with great names. Still others can be compared to the Polish small gentry, who have weight and a certain wealth, but are not included in the first-line elite.

- Clergy: mullahs and imams. They took an active part in solving public issues.

- "Thokotli" peasants. They belong to princes and uzdens, have their own land or are leased from the owners. They make up the main population of Kabarda: they are engaged in agriculture, cattle breeding, fishing, and ensure the well-being of the ruling elite.

- Slaves, or Yasyrs. Slaves were bought and used as captives as lures. The lowest, powerless layer of the population. Most were used as servants in noble houses.

Family life

Until the 19th century, Kabardians lived in a large patriarchal family, the average number was about 60 people. The head of the family was the eldest man, there was a saying: “The power of the eldest is equal to the power of God.” Honoring elders is one of the fundamental traditions of Kabardians. The oldest man, even if he was lower in class, always sat in the place of honor at the table. Other men sat down later or remained standing; sons did not have the right to eat with their father at the same table. Often in everyday life, the head of the family shared food only with his grandchildren, for whose upbringing he was responsible.

The eldest woman was considered the main one in solving household and economic affairs, and had complete power over children and daughters-in-law. Women were in a dependent position on men, but they enjoyed respect and honor and did not experience physical or moral violence. Islam allowed polygamy, but family values prescribed Kabardians to have one life partner. Divorce was viewed negatively, although men could file a request - without explanation, and women - due to infidelity or due to male impotence. There was a proverb: “The first wife is your wife, the second wife is your wife.” Researchers are ambivalent about the ritual of avoidance, which forbade daughters-in-law to talk to their fathers-in-law. There were especially strict rules regarding communication with the father-in-law. In the first years, usually before the birth of their first child, the young wife was required to cover her face in the presence of her husband’s father; she was forbidden to speak first, look into the eyes, stand with her back or opposite: only half a turn. A number of researchers consider this, coupled with the custom of bride price and arranged weddings, to be oppression of women. Others consider avoidance to be a sign of respect for daughters-in-law, a way of life that has been formed since ancient times, helping a large family to avoid interpersonal conflicts and contradictions. Avoidance also affected husband and wife, parents and children, son-in-law and spouse's parents. We did not see the latter for a month after the wedding: after the young wife was brought to visit her father’s house, the ban was lifted. The spouses did not call each other by name; it was shameful to talk about a wife or husband in front of strangers. If necessary, they would say “the son of so-and-so,” “their daughter.” The display of tender feelings was considered a disgrace; it was forbidden to remain alone in the same room during the day: spouses met at night or in the presence of other relatives.

Avoidance affected the relationship between parents and children, mostly the father. A man was forbidden to pick up a child in his arms in the presence of strangers, use gentle words, call him by name, play, caress, or kiss. Since the mother had the responsibility of caring for the baby, she was less affected by avoidance. However, according to tradition, during the first carrying out of the cradle into the common living room, the woman did not look at the child and did not approach him. The mother was forbidden to publicly mourn her child if he died. Strict avoidance, coupled with the need to create strong inter-clan and inter-tribal relationships, gave rise to the tradition of atalism. At an early age, one or more children from a family were given to be raised by an equal or slightly less noble family of their own or someone else's people. The atalyks fully provided for the pupils, gave them education and life skills. With the onset of adulthood, boys and girls were returned, provided with weapons, a horse, and outfits. Families gave rich gifts to the atalyks; often the bride price for the girl was sent to the teachers.

Classes

The traditional occupations of Kabardians were agriculture and cattle breeding. They sowed wheat, barley, just corn. They were engaged in gardening, gardening, and beekeeping. They raised small and large cattle and used transhumance technology. Buffaloes were used as draft animals. Kabardians became famous as excellent horse breeders, who bred the famous Kabardian horse-drawn breed. Horses were distinguished by their extraordinary endurance, efficiency, fearlessness, and resistance to disease, which made them indispensable on long campaigns, crossings, and battles. Being an aboriginal breed, the Kabardian horse perfectly maintained balance in mountainous areas, on rocky, slippery paths, descents, and ascents.

Carrying out a Kabardian wedding

All modern Kabardian weddings take place by mutual consent of both parties. In past times, it was legal to steal brides. And if the woman was not returned to the house before nightfall, then the parents had to give their consent to register the marriage. Otherwise, the woman would face shame. After all, it was not permissible for a young girl not to spend the night outside her home.

Conventionally, the process of registering a marriage according to Kabardian traditions can be divided into several stages:

- Any marriage among Kabardians is performed by an imam. He performs the appropriate ritual and pronounces his blessing. After this, the marriage is considered concluded. The young wife is brought to the groom's house, where they will live separately from their parents. The next morning the marriage is confirmed. To do this, sometimes, according to Muslim traditions, a sheet of the newlyweds with traces of their marital intimacy is shown for confirmation.

- During the second day, the groom's parents celebrate the wedding, sing songs, say toasts and wishes to the newlyweds, and perform traditional Kabardian dances. The next day, the bride's relatives join their celebration. They bring the bride's dowry with them. Together they plan and prepare for the formal part of the wedding.

- To register a marriage, young people come to the registry office and formalize their relationship. The parents of the parties are not present at this ceremony.

- After the registry office, the newlyweds go to celebrate the wedding at the groom's house.

A Kabardian wedding is simply imbued with traditions and customs. Even during the celebration, there are some peculiarities that people try to adhere to. Well, initially it should be noted that women and men at a wedding sit separately and celebrate separately, without interfering with each other.

The groom is placed in the center of the table with men on both sides. During the celebration, they communicate, get to know each other better and always get to know the elders. At a certain moment, the lights in the room are suddenly turned off and people sitting nearby try to take the groom’s hat off the head and steal it. The main task of the young man is to show all his ingenuity and prevent the loss of his headdress.

The bride also has her own tests and trials. Before the girl enters the festive hall, a lamb skin is spread on the floor. The bride stands on top of her, and relatives of both sides try to pull the skin from under her legs. The main task of a young wife is to stand on her feet. It may not sway much, but falling to the floor is simply unacceptable.

In the second half of the celebration, when all the rituals and tests have been completed. The newlyweds go out to dance together, and relatives and friends sprinkle millet and various coins on the couple. According to signs, this should bring prosperity and well-being to the family. During the celebration, the bride's face should be covered with a translucent fabric, because men may be present at the wedding who are not blood relatives of either the groom or the bride.

Ritual after the wedding

The Caucasian people greatly respect and honor older people. Therefore, after each wedding, another national custom is always carried out, which is called the “elopement of the old lady.” The groom's grandmother leaves the house and hides. And the young people must find her and bring her back to the house. This tradition says that in the home of the young, the old will always be honored and respected.

Religion

From the XV-XVI centuries. Kabarda is captured by Islam. A number of researchers believe that Orthodoxy was previously practiced in the region, others talk about the predominance of paganism. Echoes of traditional beliefs have survived to this day, for example, the ritual of making rain. They revered the thunder god Shible: after the first thunder in the spring, they poured water on the granaries with a request for a bountiful harvest in the new season. The god of agriculture and fertility, Tkhashkho, was considered one of the most revered in the pantheon. The full cycle of agricultural rituals is associated with it: folk festivals with animal sacrifices before plowing, the festival of the first furrow, the end of plowing, and harvesting. There was a cult of trees, the wolf was considered a sacred animal: the bones, teeth, and veins of the animal were considered amulets.

Traditions

The Kabardian wedding ritual included many stages, which ensured its significant duration: from several months to several years. The cycle included the following activities:

- Matchmaking. Relatives on the male side chose a bride worthy of her status, and they sent matchmakers to her parents. From the first time, the conversation did not always end with a positive answer: sometimes it took several months to wait for consent.

- Agreeing on the amount of dowry. Negotiations were made slowly, often with disputes and bargaining. Rich families knew the required ransom amount: a minimum of 30 parts. Eight were a servant, a helmet, chain mail, a saber, a guard, a good and an ordinary horse, and 8 bulls. The remaining 22 parts were measured by the heads of animals: rams, bulls, buffaloes.

- Bridesmaids and engagement. On the appointed day, the future bride and groom met for the first time in the bride's house, where the acquaintance took place. According to Islamic traditions, a betrothal ceremony was held.

- Payment of the share of the dowry. Depending on the financial situation of the young man’s family, the time for collecting the bride price was agreed upon. When most of the ransom was collected, it was handed over to the bride's relatives, after which the exact wedding date was set.

- Conclusion from the bride's father's house. The girl was dressed in a formal wedding suit, covering her head and face. The groom's friends arrived in a noisy wedding train to pick up the bride. Friends and relatives jokingly asked for a ransom, upon receiving which they released the bride.

- "Hide" the bride and groom in different other people's houses. The bride was brought to the house of one of the groom's friends, and he himself settled in the house of another friend. The future husband came to the girl at night, the owner of the house acted as a guard, responsible for the safety of the future spouses with his life. This situation continued for a month.

- Moving to my husband's house. The bride was secretly brought to the groom's house, settled in a room that then became the home of the young family. For a week, the girl did not leave the room and did not communicate with anyone. At this time, the groom was communicating with relatives and praising his future daughter-in-law.

- Rite of reconciliation with relatives. The ceremony of reconciliation between the groom's parents and daughter-in-law took place after her solemn exit from the room. The eldest woman in the house smeared the girl’s lips with oil and honey, sprinkled them with sweets: so that life would be full and sweet. Afterwards a general celebration was held, which lasted several days.

The wedding cycle was completed by numerous rituals of introducing the daughter-in-law to her relatives, home, and household.

Bride

After the families agreed on the bride price, they moved on to the next stage - bridesmaids. The ritual of exchanging wedding rings was not delayed for long. As soon as the groom paid part of the previously agreed upon amount of dowry, he was given the opportunity to take his beloved out of her parents’ house.

From that moment on, the bride and groom were settled in different houses. According to tradition, the future husband and relatives should not contact for some time. The rule was especially harsh in relation to the bride, groom and elders. Only after a long period of time was it possible to bring the beloved to the yearning guy. First of all, the girl examined the room where the young people would soon live. The common room was allowed to be seen after a few weeks. Kabardian weddings are about observing all traditions and rituals.

Such a superficial description is not able to reflect the spectacular rituals of the Kabardian wedding, of which in reality there are many. Unfortunately, with each new generation, traditions and rituals are gradually forgotten and lose their original content. Although modern Kabardian weddings often feature national costumes and spirited dance elements, not all indigenous residents like this. What makes them angry?