Childhood and youth

The childhood of the French-Swiss Jean-Jacques Rousseau cannot be called carefree. His mother, Suzanne Bernard, died during childbirth, leaving her son in the care of his father, Isaac Rousseau, who worked as a watchmaker and moonlighted as a dance teacher. The man took the death of his wife hard, but tried to direct his love towards raising Jean-Jacques. This became a significant contribution to the development of the younger Rousseau.

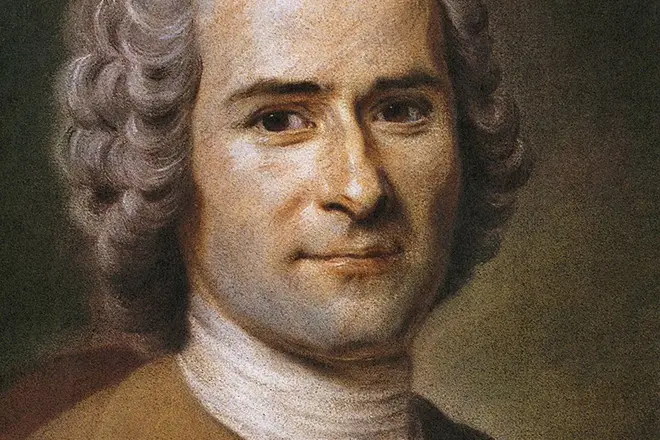

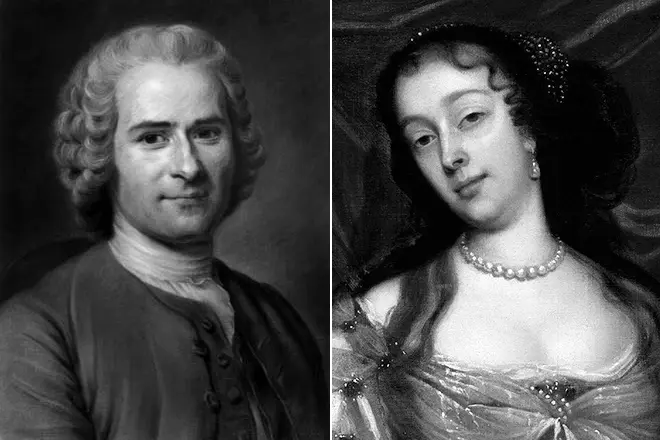

Portrait of Jean-Jacques Rousseau

From a young age, the child studied the works of Plutarch and read “Astraea” with his father. Jean-Jacques imagined himself in the place of the ancient hero Scaevola and deliberately burned his hand. Soon the elder Rousseau had to leave Geneva due to an armed attack, but the boy remained in his home with his uncle. The parent had no idea that his son would become a significant philosopher for this era.

Later, relatives sent Jean-Jacques to the Protestant boarding house Lambercier. A year later, Rousseau was transferred to a notary for training, and later transferred to an engraver. Despite his serious workload, the young man found time to read. Education taught Jean-Jacques to lie, pretend and steal.

At the age of 16, Rousseau escapes from Geneva and ends up in a monastery located in Turin. The future philosopher spent almost four months here, after which he entered the service of the aristocrats. Jean-Jacques worked as a footman. The count's son helped the guy learn the basics of the Italian language. But Rousseau received his writing skills from his “mother” - Madame de Varan.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, in some works written with his own hand, presents interesting facts from his biography. Thanks to this, we learn that the young man worked as a secretary and home tutor before he came to philosophy and literature.

Biography. Youth and early career

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, whose main ideas we are analyzing, was born in the city of Geneva and, according to his religious beliefs, was a Calvinist in his childhood. His mother died during childbirth, and his father fled the city because he became a victim of criminal prosecution. From an early age he was apprenticed, but neither the notary nor the engraver, under whose subordination the future philosopher was, loved him. The fact is that he preferred to voraciously read books rather than work. He was often punished, and he decided to run away. He came to the neighboring region - Savoy, which was Catholic. There, not without the participation of Madame de Varan, his first patroness, he became a Catholic. Thus began the ordeal of the young thinker. He works as a footman in an aristocratic family, but does not settle down there and goes back to Madame de Varan. With her help, he goes to study at the seminary, leaves it, wanders around France for two years, often spending the night in the open air, and again returns to his former love. Even the presence of another admirer of the “mother” does not bother him. For several years, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, whose biography in his youth was so different from his subsequent views, either leaves or returns to Madame de Varan and lives with her in Paris, Chambery and other places.

Philosophy and literature

Jean-Jacques Rousseau is, first of all, a philosopher. The books “The Social Contract”, “The New Heloise” and “Emile” are still studied by representatives of science. In his works, the author tried to explain why social inequality exists in society. Rousseau was the first to try to determine whether there was a contractual method of creating statehood.

Philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques considered law to be an expression of the general will. He was supposed to protect members of the public from a government that is incapable of breaking the law. Property equality is possible, but only if the general will is expressed. Rousseau suggested that people make their own laws, thereby controlling the behavior of the authorities. Thanks to Jean-Jacques Rousseau, they created a referendum, shortened the terms of parliamentary powers, and introduced a people's legislative initiative and a mandatory mandate.

"The New Heloise" is Rousseau's iconic work. The novel clearly shows the notes of Richardson's Clarissa Garlo. Jean-Jacques considered this book the best work written in the epistolary genre. "The New Heloise" presents 163 letters. This work delighted French society, since in those years this method of writing novels was considered popular.

Speech by Jean-Jacques Rousseau

“The New Eloise” tells the story of the tragedy in the fate of the main character. Chastity puts pressure on her, preventing the girl from enjoying love and submitting to the enticing temptation. The book won the love of people and made Rousseau the father of romanticism in philosophy. But the writer’s literary life began somewhat earlier. Back in the middle of the 18th century, Rousseau was in the service of the embassy in Venice. Soon the man finds a calling in creativity.

An acquaintance took place in Paris that played a significant role in the fate of the philosopher. Jean-Jacques met with Paul Holbach, Denis Diderot, Etienne de Condillac, Jean d'Alembert and Grimm. The early tragedies and comedies did not become popular, but in 1749, while imprisoned, he read about a competition in the newspaper. The topic turned out to be close to Rousseau:

“Did the development of sciences and arts contribute to the corruption of morals, or did it contribute to their improvement?”

This inspired the author. Jean-Jacques gained popularity among citizens after staging the opera “The Village Sorcerer.” This event happened in 1753. The soulfulness and naturalness of the melody testified to village morals. Even Louis XV hummed Colette's aria from the work.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

But “The Village Sorcerer” and “Discourses” added problems to Rousseau’s life. Grimm and Holbach perceived the work of Jean-Jacques negatively. Voltaire sided with the enlighteners. The main problem, according to philosophers, was the plebeian democracy present in Rousseau's work.

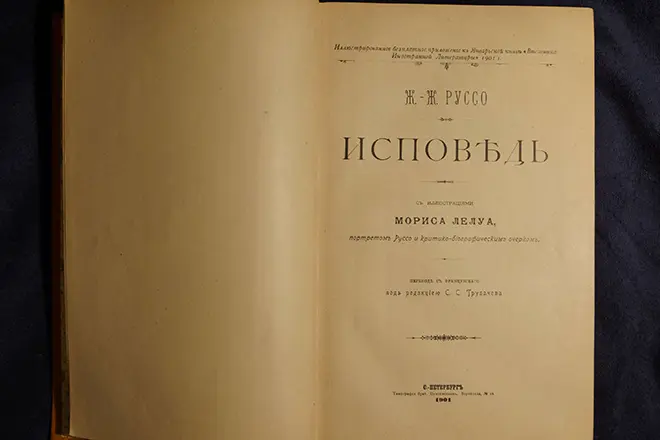

Historians have enthusiastically studied Jean-Jacques’ autobiographical work entitled “Confession.” Truthfulness and sincerity are present in every line of the work. Rousseau showed readers his strengths and weaknesses and exposed his soul. Quotes from the book are still used to create a biography of the philosopher and writer, and to evaluate the creativity and character of Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

A thinker and ideological predecessor of the French Revolution of the 18th century, Rousseau went down in history as a teacher, writer, philosopher and encyclopedist.

His views on society and the state were more than new for his time. Jean-Jacques Rousseau

(French: Jean-Jacques Rousseau) was born on June 28, 1712 in Geneva, in the family of a watchmaker. In his youth, he tried many professions - he served as a footman, scribe, tutor, music teacher..., and in 1741 he left for Paris. Here Rousseau became close to D. Diderot and other educators, collaborated in the encyclopedia, where he wrote articles mainly on music issues.

In 1750, his treatise “Discourse on the Sciences and Arts” brought the author a prize from the Dijon Academy and fame. In subsequent years, he continues to work fruitfully; his operas and plays are staged on various French stages, albeit with varying degrees of success.

But in 1762, after the publication of the pedagogical novel “Emile,” where the author developed the deistic doctrine, the wrath of the Catholic Church fell upon Rousseau, and the government ordered his arrest. And Rousseau was forced to leave France and go to England. Moreover, he was persecuted not only by French Catholics, but also by Swiss Protestants.

In addition, Rousseau had a very complex character: he was surprisingly vindictive, but at the same time he had the talent to forget about his benefactors. And towards the end of his life, suspiciousness developed in him: everywhere he saw conspiracies to cast him in an unfavorable light. In the end, the patience of even the most devoted friends was exhausted and the philosopher was shown the door.

An outlandish egoist, Rousseau was distinguished by his extraordinary vanity and pride. His reviews of his own talent, the dignity of his writings, and his worldwide fame pale before his ability to admire his personality.

Meanwhile, he really had a serious influence on many minds of the era. Perhaps it was precisely the heightened social contradictions that brought Rousseau into the arena of time. Recognizing the harmful influence of the sciences and arts, he sought in them spiritual rest and a source of glory. Having acted as an exposer of the theater, he wrote for it. Having glorified the “state of nature” and denounced society and the state as founded on deceit and violence, he proclaimed “public order a sacred right, serving as the basis for all others.”

Constantly fighting against reason and reflection, he sought the basis for a “lawful” state in the most abstract rationalism. While advocating for freedom, he recognized the only free country of his time as unfree. By handing over unconditional supreme power to the people, he declared pure democracy an impossible dream. Avoiding all violence and trembling at the thought of persecution, he hoisted the banner of the revolution in France. Rousseau remained the son of his artificial age and the master of paradox.

Thanks to the combination of passion and art, no other writer of the 18th century had such an influence on France and Europe as Rousseau. He transformed the minds and hearts of the people of his age by what he was, and even more by what he seemed.

His book "The New Heloise" was incredibly popular, as was his treatise "The Social Contract", where Rousseau described the ideal state, a free human union in which power belongs to the whole people and in which all citizens are equal.

In general, Rousseau's artistic heritage is very diverse in genres - poetry, poems, comedies, operas (for which he himself composed both the libretto and music) and other works.

He was able to return to Paris in 1770, and the writer brought with him the completed manuscript of the “Confession,” which was supposed to tell descendants the truth about himself and his enemies...

Jean-Jacques Rousseau spent the last months of his life in Ermenonville, near Paris, where he died on July 2, 1778.

Pedagogy

The sphere of interest of the enlightener Jean-Jacques Rousseau was the natural man, who is not influenced by social conditions. The philosopher believed that upbringing influences the development of a child. Rousseau used this idea when developing a pedagogical concept. Jean-Jacques presented the main pedagogical ideas in his work “Emile, or On Education.” This treatise, according to the author, is the best and most important. Through artistic images, Rousseau tried to convey thoughts regarding pedagogy.

The educational system did not suit the philosopher. Jean-Jacques's ideas were contradicted by the fact that these traditions were based on churchliness, and not democracy, which was widely spread in those years in Europe. Rousseau insisted on the need to develop natural talents in children. The natural development of the individual is the main task of education.

According to Jean-Jacques, views on raising children must change radically. This is due to the fact that from the moment of birth to death, a person constantly discovers new qualities in himself and the world around him. Based on this, it is necessary to build educational programs. A good Christian and a respectable person are not what a person needs. Rousseau sincerely believed that there are oppressed and oppressors, and not the fatherland or citizens.

Book by Jean-Jacques Rousseau

The pedagogical ideas of Jean-Jacques Rousseau consisted of advice to parents about the need to develop in a little person the desire to work, self-respect, a sense of freedom and independence. Under no circumstances should you indulge or give in to demands, even the whims of children. At the same time, one must refuse to subordinate the child. But most of all, the philosopher was worried about shifting the responsibility for upbringing to a teenager.

Labor plays an important role in the upbringing of a person, which will instill in the child a sense of duty and responsibility for his own actions. Naturally, this will help the baby earn food in the future. By labor education, Rousseau meant the mental, moral and physical improvement of a person. The development of the child's needs and interests should be of paramount importance to parents.

Thinker Jean-Jacques Rousseau

According to Jean-Jacques Rousseau, at each stage of growing up, it is necessary to cultivate something specific in a child. Up to two years – physical development. From 2 to 12 - sensual, from 12 to 15 - mental, from 15 to 18 years - moral. The main task before the father and mother is to be patient and persistent, but in no case should they “break” the child by instilling in him the false values of modern society. Physical exercises and hardening will develop stamina, endurance and improve health in the baby.

During the period of growing up, a teenager needs to learn to use his senses, not books, to understand the world. Literature is good, but it puts someone’s vision of the world into fragile minds.

Thus, the child will not develop his own reason, but will begin to take the words of others on faith. The main ideas of mental education were communication: parents and educators create an atmosphere where the child wants to ask questions and get answers. Rousseau considered geography, biology, chemistry and physics to be important subjects for development.

Growing up at 15 years old means constant emotions, outbursts of feelings that overwhelm teenagers. During this period, it is important not to overdo it with moralizing, but to try to instill moral values in the child. Society is quite immoral, so there is no need to shift this responsibility to strangers. At this stage, it is important to develop kindness of feelings, judgment and will. It will be easier to do this away from big cities with their temptations.

Book by Jean-Jacques Rousseau

As soon as a boy or girl turns 20, it is necessary to move on to becoming familiar with public responsibilities. Interestingly, female representatives were allowed to skip this stage. Civic responsibilities are an exclusively male activity. The works of Jean-Jacques Rousseau reveal an ideal of the individual that was at odds with 18th-century society.

Rousseau's works revolutionized the pedagogical world, but the authorities considered it dangerous, threatening the foundations of the public worldview. The treatise “Emile, or On Education” was burned, and a decree of arrest was issued against Jean-Jacques. But Rousseau managed to hide in Switzerland. The philosopher's thoughts, despite being unacceptable by the French government, influenced the pedagogy of that time.

RUSSO

Portrait of J. J. Rousseau by M. C. de Latour (1753). Museum of Art and History (Geneva).

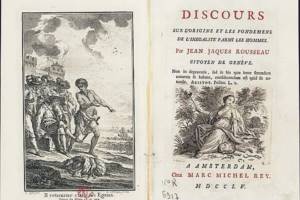

ROUSSEAU (Rousseau) Jean Jacques (28.6.1712, Geneva - 2.7.1778, Ermenonville, near Paris; in 1794 R.'s ashes were transferred to the Pantheon), French. writer, philosopher, composer. The son of a Calvinist watchmaker. Independently studied various. crafts, read a lot; served as a footman, tutor, music teacher, and home secretary. During his travels he became close to the Swiss. noblewoman L. de Varan, in whose house he lived intermittently during the 1730s, studied history, philosophy, mathematics, botany and music, and under whose influence he accepted Catholicism. Until the end of his life he made money by copying music. In 1741 he came to Paris. In 1743–44 secretary of the French. ambassador in Venice. From 1749 he wrote for the Encyclopedia, published by D. Diderot and J. D'Alembert (mainly articles on music, which raised objections from J. F. Rameau), but the philosopher. and societies. R.'s views differed from the views of older encyclopedists. While the Enlighteners (see Enlightenment) connected social and morals. progress with the development of science, R. contrasted nature and civilization, the “natural state” and the “social”, arguing that the closer a person is to nature (where there is no industry, sciences and arts), the purer and more virtuous he is: the treatise “Discourse about the sciences and arts” (“Discours sur les sciences et les arts”, 1750, Russian translation 1768), which brought him fame. R. condemned Voltaire's proposal to open a theater in Geneva and disputed D'Alembert's assertion that theatrical performances contribute to the purification of morals ("Letter to D'Alembert on spectacles", "Lettre à M. D'Alembert sur les spectacles", 1758). Having broken off relations with Diderot, d'Alembert and Voltaire, R. focused on criticizing existing social norms as contrary to nature and on asserting the need to return to the “natural state,” which he thought of as the initial stage of human existence, marked by freedom, equality and virtue: treatise “Discourse on the origin and foundations of inequality between people” (“Discours sur l'origine et les fondements de l'inégalité parmi les hommes”, 1755, Russian translation 1770). R. saw the cause of social inequality in the basis of citizenship. society of private property, which was absent in the “state of nature.” Realizing, however, that it is impossible to return to this state and that only the ownership of private property turns an individual into a responsible member of society, R. in the treatise “On the Social Contract, or Principles of Political Law” (“Du contrat social ou principes du droit politique”, 1762 , Russian translation 1903), which brought him the greatest, albeit posthumous, fame, substantiated the need to conclude an agreement between people during the transition from the natural state to the social one. Unlike other concepts of the social contract of the 17th and 18th centuries, R. did not propose an agreement between the ruler and his subjects, but an agreement between equal individuals with each other or society as a whole with each of the individuals that make it up (“all of them assume obligations on the same under the same conditions and everyone should enjoy the same rights"). Ch. the concepts of the treatise are “sovereign” and “general will”. The people bearing the burden of legislating. power, R. was declared a “sovereign”, whose power is indivisible and inalienable; Deputies are recognized only as representatives of the people, having an exclusively advisory voice. The adoption of laws - acts of the “general will” - requires an assembly of all citizens (direct democracy), while the people cannot be the creator of laws: they need a legislator who understands human weaknesses, but is not subject to any of them. When the monarchy turns into despotism, and the equality of all citizens turns out to be the equality of all before the tyrant, a violent overthrow of despotism is possible: R. allowed both revolution and dictatorship as measures necessary to save the fatherland, but considered them extreme and short-term means. R.'s views and writings were condemned by the Paris Parliament, and then by the authorities of Geneva; he took refuge from persecution in Motiers (near Neuchatel), and in 1766, at the invitation of D. Hume, he left for England. Returning to Paris in 1767, R. suffered from persecution mania in the last years of his life and lived under the guardianship of the Marquis R. L. Girardin in his castle in Ermenonville.

As a writer, R.’s fame was brought to him by the epistolary novel “Julie, or the New Eloise” (“Julie ou la Nouvelle Héloise”, 1761, abbr. Russian translation 1769; Russian translation 1803–04), written under the influence of S. Richardson and contributed to the development of sentimentalism in France. In it, in line with the theoretical. R.'s views present the story of the noblewoman Julia's love for her teacher Saint-Pré - an humble man, but noble and virtuous, as well as the story of her marriage not out of love, but at the will of her father, and death; subtle psychologism of the novel, description of the “life of the heart” and virtuous sensitivity of ch. heroes are combined with social criticism. Psychological the prose of romanticism was anticipated by “Confessions” (“Les Confessions”, 1765–70, published in 1782–89, abbr. Russian translation 1797), in which R. showed himself “in all the truth of nature.” His later works are also largely autobiographical: “Rousseau judges Jean-Jacques” (“Rousseau juge de Jean-Jacques”, 1772–75), “Walks of a lonely dreamer” (“Les Rêveries du promeneur solitaire”, 1776). Among other lit. works: poetic. collections, comedies “Narcissus” (“Narcisse”, 1733, published in 1752, published in 1753), “Prisoners of War” (“Les prisonniers de guerre”, 1743, published in 1782).

Pedagogical R.'s views were reflected in the book. “Emile, or On Education” (“Emile, ou De l'éducation”, 1762, abbr. Russian translation 1779), combining the features of a treatise and an artistic work. a work in which, using the example of the story of the title character R., as opposed to bookish secular education, he proposed a special system for the formation of the “heart” rather than the “mind” through work and communication with nature. Change society. way of life, a semblance of “natural” orders can be recreated, according to R., either by a revolutionary. violence, or education and proper upbringing; The well-being of not only the state, but also of each individual depends on correct upbringing. The mind of a sage, the strength of an athlete, hard work, skills of a useful craft, immunity to the temptations of civilization, prejudices and bad influences, the ability to control oneself, to balance desires with capabilities - these are the qualities of a perfect person. Each person has a unique physical. and mental a warehouse that requires an individual approach from the teacher, therefore each child must have his own mentor, who is both an educator and a teacher. The model of natural sciences set forth in “Emil” and other works of R. education was largely hypothetical. According to R., he tried to give a non-practical. recommendations, but to depict an ideal to which to strive. Pedagogical R.'s theory had a significant impact on education systems in the field. 18 – beginning 19th centuries

R.'s “Musical Dictionary” (“Dictionnaire de musique”, 1768, reprinted several times, including in foreign languages) is one of the most authoritative in the 18th century. reference publications about music. Music R.'s aesthetics are close to the ideas of the encyclopedists: he preached simplicity, naturalness, direct emotionality and argued that the basis of music is melody. In the “Buffon War” that broke out in Paris in 1752, he took a pro-Italian position (he published at his own expense the score of “The Maid and Lady” by G.B. Pergolesi, and in 1753 he published a polemical “Letter on French Music”). Sargent criticism of the French. Baroque opera was also contained in R.’s novel “Julia, or the New Heloise.” In the last years of his life he came out in support of the opera reform of K.V. Gluck. R.'s one-act opera “The Village Sorcerer” (“Le devin du village”, in his own text; Fontainebleau, 1752) is one of the first works of the comic-opera genre. The premiere of the melodrama “Pygmalion” (text by R., music co-authored with O. Coignet; Lyon, 1770) gave birth to a fashion for this genre in Europe. Author of several motets, 3 collections of vocal pieces, etc.

R.'s influence on the west. the culture is very great; his teaching laid the foundation for a broad ideological and philosophical philosophy. movement - Rousseauism, which popularized the myth of the “virtuous savage”; political R.'s views contributed to the development of democracy, had a significant influence on T. Jefferson and other leaders of the War of Independence in North America (1775–83), and were the ideological basis for the radical movements of the French Revolution of the 18th century. Dept. the language of the “Social Contract” was included in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen. R.'s works have been widely known in Russia since the 18th century; among his most prominent admirers are M. V. Lomonosov, N. M. Karamzin, L. N. Tolstoy; A. S. Pushkin in the novel “Eugene Onegin” called R. “an eloquent madman” and “a defender of liberties and rights.”

Personal life

Due to lack of money, Jean-Jacques did not have the opportunity to marry a noble lady, so the philosopher chose Therese Levasseur as his wife. The woman worked as a maid in a hotel located in Paris. Teresa was no different in intelligence and intelligence. The girl came from a peasant family. I didn’t receive an education - I didn’t know what time it was. In society, Levasseur appeared vulgar.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Therese Levasseur

Nevertheless, Rousseau lived in marriage until the end of his days. After 20 years of married life, the man and Teresa went to church, where they were married. The couple had five children, but the kids were immediately sent to an orphanage. Jean-Jacques explained this act by the lack of funds. And besides, according to the philosopher, children prevented Rousseau from doing what he loved.

Moving to Paris

For some time, Jean-Jacques Rousseau lives with his mistress in the villa, but, unfortunately, he no longer feels so easy and free in her company. He understands perfectly well that he turns out to be a “third wheel” for the couple, so six months later he gets a job as a home teacher for the Mably family from Lyon. But even there he does not find peace: the education of the younger generation is difficult, and the “teacher” devotes more time to the master’s wine, which he steals into his room at night, and to the master’s wife, whom he “makes eyes on.” After a serious scandal, Russo is kicked out.

He decides to move to Paris and demonstrate there his manuscript entitled “Discourse on Modern Music,” according to which Jean-Jacques proposed writing down notes in numbers for greater convenience. His theory fails, and Rousseau again faces the fact of a poor and worthless existence.

The French tax farmer Frankel takes pity on Rousseau and offers him the position of secretary at his place. The writer agrees and from that moment on becomes the best friend of the Frankel family. Thanks to his ability to speak beautifully, he charms the audience with beautiful stories about his own travels, half of which he brazenly makes up. In addition, he even stages several vulgar performances that tell some periods of his life. But any tactlessness is forgiven for his innate charisma and excellent oratorical abilities.

Death

Death overtook Jean-Jacques Rousseau on July 2, 1778, at the country residence of Chateau d'Hermenonville. A friend brought the philosopher here in 1777, who noticed a deterioration in Rousseau’s health. To entertain the guest, a friend organized a concert on an island located in the park. Jean-Jacques, having fallen in love with this place, asked to make a grave for him here.

The friend decided to fulfill Rousseau's last request. The official burial place of the public figure is Willow Island. Hundreds of fans visited the park every year to meet the martyr, whom Schiller so vividly described in poems. During the French Revolution, the remains of Jean-Jacques Rousseau were transferred to the Pantheon. But 20 years later, a bad event happened - two criminals stole the philosopher’s ashes at night and threw them into a pit filled with lime.

[edit]Also

- In the eighth volume of the light novel about Haruhi Suzumiya, the SOS Brigade investigates a case of strange behavior of local animals. Kyon and Haruhi's classmate Sakanaka, who has a dog named after Jean-Jacques Rousseau, asks to take over the case.

| “You know, Russo was the first to sense something was wrong,” Sakanaka said, turning to Haruhi. - Rousseau? — Haruhi, of course, wrinkled her brow. - Yes. Our pet dog, Russo. Well, the dog has a name. |

| Nagaru Tanigawa . The indignation of Haruhi Suzumiya. Wandering Shadow |

- But the racially Armenian singer with his mouth Abraham Russo definitely has nothing to do with the famous philosopher.