Childhood and youth

The writer was born in January 1883 in the city of Nikolaevsk, Samara province. The childhood of the author of “Count Cagliostro” and “Walking in Torment” was spent on the estate of an impoverished landowner who served in the zemstvo government, Alexei Bostrom, on the Sosnovka farm near Samara.

Portrait of Alexei Tolstoy

Who was the genetic father of Alexei Tolstoy is still debated today. The writer's mother, Alexandra Leontyevna Turgeneva, ran away from her husband, a wealthy Samara landowner, an officer in the Life Guards Hussar Regiment and Count Nikolai Alexandrovich Tolstoy, while pregnant. She went to Bostrom, leaving her husband three children. Biographers and contemporaries of Alexei Tolstoy called landowner Bostrom the father of the writer. Until the age of 13, the prose writer bore his last name and considered him his own father. Alexandra Leontievna never married Alexei Bostrom: the church did not allow it.

Alexey Tolstoy in childhood

When Alyosha grew up, his mother began a 4-year lawsuit, wanting to return her son's title of count, surname and patronymic of her first husband. The litigation ended on Alexei Nikolaevich’s 17th birthday: in 1901, he became Count Tolstoy, not knowing the person whose patronymic and surname he got.

The love of literature and writing was instilled in Alexei Tolstoy by his mother, the great-niece of Nikolai Turgenev. She signed her works - novels and children's books - with the pseudonym Alexandra Bostrom.

Alexey Tolstoy in his youth

The future author of “The Hyperboloid of Engineer Garin” received his initial education at home. But in 1897 the family moved to Samara, where Tolstoy became a student at a real school. In 1901, the young man continued his education in St. Petersburg, entering the Faculty of Mechanics of the Technological Institute.

Biography[ | ]

Alexei Tolstoy (Samara, 1900)

Alexei Tolstoy was born to the wife of Count Nikolai Alexandrovich Tolstoy (1849-1900), but some biographers attribute paternity to his unofficial stepfather, Alexei Apollonovich Bostrom (1852-1921). Mother - Alexandra Leontievna (1854-1906), née Turgeneva - writer, grand-niece of the Decembrist Nikolai Turgenev, at the time of the birth of A. N. Tolstoy, she left her husband for A. A. Bostrom, whom she could not officially marry due to the definition spiritual consistory[5].

The emigrants Ivan Bunin, Roman Gul, and Nina Berberova doubted Tolstoy’s title of count; their opinion on this issue, however, cannot be considered unbiased.

Bunin, in his penultimate diary entry dated February 23, 1953, spoke precisely on this matter: “ Yesterday Aldanov said that Alyoshka Tolstoy himself told him that he, Tolstoy, bore the surname Bostrom until the age of 16, and then went to his imaginary father, Count Nik . Tolstoy and begged him to be legitimized as Count Tolstoy

»[6].

Roman Gul in his memoirs claims that A.N. Tolstoy was not the biological son of Count Nikolai Tolstoy (referring to the other, undisputed sons of the count[7]).

Alexey Varlamov (author of Tolstoy’s biography, published in 2006 in the ZhZL series) points out that Gul’s testimony raises serious doubts (given the memoirist’s negative attitude towards A.N. Tolstoy). The same author cites the written testimony of Alexandra Leontyevna Tolstoy - two letters written by her to Bostrom dated April 3 and 20, 1883, from which it followed that the real father of the child was Count Tolstoy, and the conception occurred as a result of rape[8]. However, the same author provides written evidence in favor of another version: Alexandra Leontievna Tolstaya at one time swore to the archpriest of the Samara church that the child’s father was Bostrom[5]. Perhaps later Alexandra Leontyevna realized that it was much better for her son to be a legitimate count, and began a long-term lawsuit about the legality of his birth, surname, patronymic and title. This litigation ended in success only in 1901, when A. N. Tolstoy was already 17 years old[5].

Sergei Golitsyn in his book “Notes of a Survivor” states: “I remember one story from Uncle Alda from his archival searches. Somewhere he unearthed a copy of an appeal from the mother of the writer A.N. Tolstoy in the royal name: she asks to give her young son the surname and title of her husband, with whom she had not lived for many years. It turned out that the classic of Soviet literature was not at all the third Tolstoy. The uncle showed this document to Bonch. He gasped and said: “Hide the paper and don’t tell anyone about it, it’s a state secret.”[9]

The future writer spent his childhood on the small estate of A. A. Bostrom on the Sosnovka farmstead, not far from Samara (currently the village of Pavlovka in the Krasnoarmeysky district).

In 1897-1898 he lived with his mother in the city of Syzran, where he studied at a real school. In 1898 he moved to Samara. In 1901 he received a matriculation certificate and left for St. Petersburg.

Museum-estate of A.N. Tolstoy in Samara

In the spring of 1905, while a student at the St. Petersburg Institute of Technology, he went to practice in the Urals, where he lived in Nevyansk for more than a month. Later, in the book “The Best Travels in the Middle Urals: Facts, Legends, Traditions,” Tolstoy dedicated his very first story “The Old Tower” (1908) to the Nevyansk Inclined Tower. In those same years, Alexey Tolstoy tried to write poetry. He even published the poetry collection “Lyrics” at his own expense in 1907, and in 1911, a book of poems based on Russian folklore, but subsequently he was not interested in poetry. Shortly before defending his diploma at the institute, he dropped out of school and devoted himself entirely to creativity.

On November 22, 1909, Alexey Tolstoy was Voloshin’s second in his duel with Gumilyov due to a misunderstanding about gossip about the young poetess Elizaveta Dmitrieva, which was written about a lot in the newspapers. But everything turned out well; the event did not affect Tolstoy’s literary reputation[10].

Tolstoy’s first plays were staged on the stages of Moscow theaters: “Rapists” - at the Maly Theater (September 30, 1913), “Cuckoo’s Tears” (under the title “Shot”) - on the stage of the K. N. Nezlobin Theater (October 20, 1914).

During the First World War, he was a war correspondent for a Russian newspaper (due to health problems, he was exempt from military service). Traveled to France and England (1916).

He welcomed the February Revolution, but did not accept the October Revolution. In August 1918, together with his wife and son Nikita, he left for Kharkov, then to Odessa. In April 1919, the Tolstoys emigrated. He was in exile in 1919-1923, first in Constantinople and Paris, from October 1921 to July 1923 in Berlin[11]. During the period of emigration, Tolstoy created the first part of the trilogy “Walking in Torment” - the novel “Sisters” (1922), the story “Count Cagliostro” (1921), the autobiographical story “Nikita’s Childhood” (1922) and the fantasy novel “Aelita” (1923) .

Subsequently, the impressions of emigration were reflected in Tolstoy’s satirical stories “The Adventures of Nevzorov, or Ibicus” (1924), “Emigrants” (1930) and the story “Black Friday” (1924). In May 1923, Tolstoy made a short trip to Russia, where he met an unexpectedly warm welcome, and later returned to his homeland forever[12].

In 1927, he took part in the collective novel “Big Fires,” published in the magazine “Ogonyok.” At the same time, he completed work on the science fiction novel “Engineer Garin’s Hyperboloid.” In 1928, the novel “The Eighteenth Year” was published - the second book in the trilogy “Walking Through Torment”.

Memorial plaque to A. N. Tolstoy in Moscow at the address: Spiridonovka street, building 4, building 1.

In 1934, he took part in the preparation and holding of the First All-Union Congress of Soviet Writers, at which he made a report on drama. As a member of the board of the Writers' Union in 1936, he took part in the persecution of the writer Leonid Dobychin,[13] which may have led to the latter's suicide.

In the 1930s, he regularly traveled abroad (Germany, Italy - 1932, Germany, France, England - 1935, Czechoslovakia - 1935, England - 1937, France, Spain - 1937). Participant of the First (1935) and Second (1937) Congress of Writers in Defense of Culture.

In August 1933, as part of a group of writers, he visited the open White Sea-Baltic Canal and became one of the authors of the memorable book “White Sea-Baltic Canal named after Stalin” (1934).

On June 20, 1936, together with members of the government commission, Alexei Tolstoy carried an urn with the ashes of Maxim Gorky across Red Square. In 1936-1938, after the death of Gorky, he temporarily headed the Union of Writers of the USSR. Since 1937 he became a deputy of the Supreme Council of the USSR of the 1st convocation, and since 1939 - an academician of the USSR Academy of Sciences.

On June 17, 1941, he addressed a letter to Stalin, in which he was interested in the possibility of Bunin returning to his homeland, as well as providing him with financial assistance [14]:

Dear Joseph Vissarionovich, I am writing to you with an important question that worries many Soviet writers. - Could I answer Bunin’s postcard, giving him hope that his return to his homeland is possible? If this is impossible, then could the Soviet government provide him with financial assistance? With deep respect and love, Alexey Tolstoy

On June 22, 1941, he completed work on the final part of the trilogy “Walking Through Torment” - “Gloomy Morning”.

One of the actual co-authors of the famous Molotov-Stalin address of 1941, in which Soviet leaders urge the people to turn to the experience of their great ancestors:

Let the courageous image of our great ancestors - Alexander Nevsky, Dimitry Donskoy, Kuzma Minin, Dimitry Pozharsky, Alexander Suvorov, Mikhail Kutuzov - inspire you in this war!

— Stalin’s speech at the Red Army parade on November 7, 1941[15]

During the war, Alexey Tolstoy wrote about sixty journalistic materials (essays, articles, appeals, sketches about heroes, military operations), starting from the first days of the war (June 27, 1941 - “What we defend”) until his death, at the end winter of 1945. The most famous work of Alexei Tolstoy about the war is considered to be the essay “Motherland”.

In the fall of 1941, the writer was evacuated near Gorky and lived for more than two months (during September-November) at the dacha in the Zimenki sanatorium on the banks of the Volga[16].

During the war, he continued to create the historical novel Peter the Great, which he began in 1929.

On March 30, 1943, the Izvestia newspaper published a letter from Tolstoy to Stalin asking for one hundred thousand rubles from the Stalin Prize for the novel “Walking Through Torment” to build a tank. Below the editors posted Stalin’s answer, which ended like this:

| Your wish will be fulfilled. I. Stalin |

Member of the Commission for the Investigation of the Atrocities of the Nazi Occupiers. Attended the Krasnodar trial.

The grave of A. N. Tolstoy at the Novodevichy cemetery. Sculptor G. Motovilov in

A. N. Tolstoy died on February 23, 1945, at the age of 63, from lung cancer. On February 24, the body was cremated. The farewell took place on February 26 in the Small Hall of the House of Unions, then the urn with the ashes was buried at the Novodevichy cemetery (site No. 2)[17][18]. The ceremony ended with a farewell salute and the Anthem of the Soviet Union.

Literature

A collection of Tolstoy's poems, Lyrics, was published in 1907. Critics noted the influence of Nikolai Nekrasov and Semyon Nadson in the early work of 24-year-old Alexei Tolstoy: the young writer imitated the masters. Later, Alexey Nikolaevich was ashamed of the authorship of the collection and tried not to remember the poems.

Writer Alexey Tolstoy

The first story, “The Old Tower,” appeared after a trip to the Urals, where the student was sent for internship. For a month and a half, Alexei Tolstoy lived in ancient Nevyansk, where he collected legends and historical information about the region and its attractions, including the Nevyansk Leaning Tower.

In 1907, Alexey Nikolaevich left the institute and devoted himself to writing. According to Tolstoy, he “attacked his theme,” suggested by the stories of his mother and relatives: it was the passing world of the nobility, whose representatives the writer called “colorful and absurd eccentrics.”

The collection of novels and stories “Trans-Volga” was received favorably by critics, including Maxim Gorky, but Alexei Tolstoy was dissatisfied with the result, calling himself “an ignoramus and an amateur.”

During his student years, Tolstoy, under the influence of Alexei Remizov, took up the task of improving the language. The richest material turned out to be ancient fairy tales, folklore, the works of Avvakum and judicial acts of the 17th century. Soon, “Magpie Tales” and the second (last) poetry collection “Beyond the Blue Rivers” appeared.

Alexei Tolstoy did not write any more poetry. But stories, fairy tales, tales and novels were born in huge quantities - the writer worked tirelessly, surprising his colleagues with his incredible efficiency. In 1911, he wrote the novel “Two Lives”, the following year the novel “The Lame Master” appeared, then the story “Behind the Style” and short stories. Tolstoy's plays were staged at the capital's Maly Theater. At the same time, the writer managed to attend parties, opening days, salons and all theater premieres.

Alexey Tolstoy and Mikhail Sholokhov

The First World War made Alexei Tolstoy a war correspondent: he wrote front-line essays for the newspaper Russkie Vedomosti and visited France and Britain. In 1915-16, the stories “On the Mountain”, “Under the Water”, and “The Beautiful Lady” appeared. The writer also did not forget about drama – in 1916 the comedies “Evil Spirit” and “Killer Whale” were released.

Alexey Tolstoy received the revolutionary events of October 1917 with caution. In the summer of 1918, he moved his family to Odessa to escape the Bolsheviks. The story “Count Cagliostro” and the comedy “Love is a Golden Book” appeared in the southern city.

Portrait of Alexei Tolstoy. Artist P.D. Corinne

From Odessa, the Tolstoy family emigrated to Constantinople, then to Paris. The move did not affect the writer’s performance: Alexey Tolstoy continued to work without straightening his back. The story “Nikita’s Childhood” and the first part of the trilogy “Walking Through Torment” were born in France.

Life abroad seemed dreary and uncomfortable to the Russian writer. Accustomed to luxury and comfort, Count Tolstoy was burdened by the unsettled life. In the fall of 1921, he moved his family to Berlin, where he stayed for two years. Alexei Nikolaevich's relations with the emigrant world deteriorated.

Alexey Tolstoy

At the end of the summer of 1923, Alexei Tolstoy returned to Soviet Russia forever. His return caused a stormy and controversial reaction: emigrant circles called the act a betrayal and showered the “Soviet count” with curses. The Bolsheviks accepted the writer with open arms: Tolstoy became a personal friend of Joseph Stalin, a regular at Kremlin receptions, received membership of the Academy of Sciences, and was elected a deputy of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR. Alexey Nikolaevich didn’t just accept it, he resigned himself to the new system as if it were inevitable. He was given an estate in Barvikha and given a car with a driver.

Alexey Tolstoy finalized the trilogy “Walking through Torment” and presented dozens of essays to young readers. For children, he remade Carlo Collodi's fairy tale about the adventures of Pinocchio, calling his story “The Golden Key, or The Adventures of Pinocchio.”

Alexey Tolstoy at work

In 1924, a story was born that literary critics consider Alexei Tolstoy’s best work - “The Adventures of Nevzorov, or Ibicus.” The writer gave the world fascinating fantastic works - the novels “Aelita” and “Engineer Garin’s Hyperboloid”, the utopian story “Blue Cities”. But readers received the fantastic works of “comrade count” with caution, and colleagues - Ivan Bunin, Korney Chukovsky, Yuri Tynyanov - with skepticism. Only Maxim Gorky appreciated the author's new novels, who predicted glory for novels in the fantasy genre.

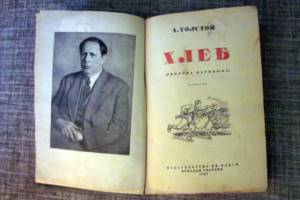

In 1937, Alexei Tolstoy wrote the story “Bread,” in which he spoke about Stalin’s outstanding role in defending Tsaritsyn during the civil war. But the main book that the writer worked on for the last 16 years of his life was the historical novel Peter the Great. After reading the work, even Ivan Bunin, who was stingy with compliments and did not like Tolstoy, became generous with his praise.

Alexei Tolstoy's story "Bread"

During the Great Patriotic War, Alexei Tolstoy wrote the drama-duology “Ivan the Terrible” and the story “Russian Character”.

But there are works attributed to the pen of the “red count”, which he disowned, not wanting to admit authorship. This is the erotic story “Bath”, which is called the first pornographic work of pre-revolutionary Russia. But no confirmation was found that the story was written by Alexei Tolstoy: there were no traces of the work left in the writer’s letters or drafts. Some critics suggest that Bathhouse was written by Leo Tolstoy, but there are also those who point to Nikolai Leskov.

Still from the film “Walking in Torment”

Perhaps Alexey Nikolaevich was among the “suspects” due to a reasonable assumption about the authorship of another work, which also contains elements of pornography. This is “Vyrubova’s Diary”, which appeared in 1927 - a vulgar libel written (allegedly) by Alexei Tolstoy and Pavel Shchegolev at the request of the authorities to discredit the royal family.

The works of Alexei Tolstoy have been filmed. Some (“The Lame Master”, “Walking Through Torment”) 3-4 times. The films “Formula of Love”, “Peter the First”, “Peter’s Youth”, “Golden Key”, “Aelita”, “Engineer Garin’s Hyperboloid” and “Nikita’s Childhood” are based on the works of the “Soviet count”.

Failed conspiracy

70 years ago, in October 1944, Alexei Tolstoy, shortly before his death, revealed to his eldest son a secret that he could not bear to bear. 20 years ago, on October 19, 1994, my father died, having managed to reveal this secret to me. It's time to share the story.

About thirty years ago, in what was then Leningrad, Yuri Mikhailovich Lotman spoke at the Pushkin Conference. He began his report like this: “We will try to reconstruct one Pushkin plan, from which very little has reached us: one word.”

A laugh went through the hall.

“This is a word,” Lo continued. It’s interesting how you tell things,” he muttered: “I told you all this.”

Whether this is true or not, among many things Tolstoy told his son the following. During a trip to Katyn and the North Caucasus as part of the Extraordinary State Commission to establish and investigate the atrocities of the Nazi invaders, Alexey Tolstoy spent several hours every day communicating with investigators, doctors, officials and high-ranking officials of the NKVD who led the forensic examination. For several weeks, together with the rest of the group, he was present at interrogations, surveys, opening burial grounds and, like everyone else, signed endless protocols establishing the guilt of the Nazis.

It is clear that the members of the State Commission themselves did not hold shovels in their hands, did not conduct ballistic experiments and did not subject the remains of Polish officers to forensic analysis. (The commission included the only lawyer Trainin, the others were party leader Andrei Zhdanov, academicians historian Evgeniy Tarle, neurosurgeon Nikolai Burdenko, hydroelectric power engineer B.E. Vedeneev, biologist Trofim Denisovich Lysenko, Metropolitan of Kiev and Galicia Nikolai (Yarushevich) and pilot Valentina Grizodubova. Chairman commission - Nikolai Shvernik).

But in an atmosphere of continuous multi-day communication, the members of the commission, having breakfast, lunch and, especially, dinner, after midnight - with a lot of vodka - got used to each other day by day, almost converged. And one day, after drinking, more confidential conversations began, at first gradually, than before. And, as Alexey Tolstoy, completely depressed by everything he saw and heard, told his son, it became absolutely clear to him and some other members of the commission that a number of crimes were committed not by the Nazis, but by NKVD officers. In any case, this was clear in relation to the Katyn executions.

The second crime that my father remembered from that conversation half a century ago was the mass death of Soviet children who were vacationing in the summer of 1941 in pioneer camps in the North Caucasus. Alexei Tolstoy said that many who were interrogated by the commission’s investigators, confident that the state wanted to establish the truth, were bold and testified that the pioneers died not so much as a result of the tragic circumstances of wartime, but because of the betrayal of party and state officials of the Stavropol region, who downloaded the provided They were loaded with all sorts of property and goods and ran away from resort areas, abandoning children and teenagers to their fate.

Now all the newspapers bore, among others, the signature of the writer Alexei Tolstoy, who with his authority confirmed the unreliable conclusions of the State Emergency Commission. And this moral trap stung Alexei Tolstoy most of all. The fact that false historical dramas came from his pen was, apparently, something he allowed himself to do as an element of a private, literary endeavor, but the fact that he was forced to participate in real, not fictitious events and with his own hands to create a false documentary history of his people - this is what became the subject of his torment.

Psychologists know that type of merry fellows and cynics who are not able to bear a major grief met head-on. And when the period of reports and evidence arrived, the writer was forced to put his signature on all official documents. These mont Blancs of falsifications, hasty manipulations and falsehoods - against the backdrop of the real tragedy of the country and the people, this forever buried truth - this is what he morally worried about most.

The pipe, according to Vadim Baranov's hypothesis, was poisoned

In the late 90s, an article by literary critic Vadim Baranov appeared in Literary Gazette, which put forward a hypothesis about the cause of the early death of Alexei Tolstoy (at 63 years old). Baranov suggested that the writer was poisoned in a cunning way. He was invited by Comrade Stalin to a conversation, at the end of which the leader invited him to exchange handsets. Tolstoy, of course, could not refuse; he returned home, showed Stalin’s pipe to his close friends and lit it with demonstrative pleasure. The pipe, according to Vadim Baranov's hypothesis, was poisoned. Hence - lung sarcoma and quick death.

Some time ago, my relatives and I sent a lock of Alexei Tolstoy’s hair (kept in the family) for a private chemical examination. The examination showed that the hair was free from any presence of former poison.

Alexey Tolstoy

It is always important to get such an answer. But it seems to me that the matter is not at all in the deadly poison. That mental and ideological shock, that, in modern terms, severe stress that the writer experienced, who was caught selling his soul to Leviathan, was not in vain for him. Modern medicine increasingly puts the psychological causes of cancer in first place. In this case, one’s own sick conscience turned out to be stronger than poison.

My father considered this part of his conversation with Alexei Tolstoy to be the most important. In 1993, a lot was said in the Russian press on the topic of Katyn and other Stalinist crimes. High school students began to understand the history of terror better than their father, who survived this terror. And, it seems to me that he had a sort of motive of jealousy: you all here learned about Stalin’s atrocities only recently, but I carried this secret in my soul for half a century. I think he had a similar motive.

But for me this kind of confession was less interesting than another story, alas, much less detailed. My father himself did not attach serious importance to it. To me, especially now, it seems quite promising for understanding that hole in the burnt tissue that is called the history of Soviet literature.

There were about two and a half thousand denunciations against you in the Case

Then, during the days of the trip to Katyn and the North Caucasus, one of the high-ranking officials of the NKVD said to Alexei Nikolaevich: “Do you know why you were not arrested before the war? After all, there were about two and a half thousand denunciations against you in the Case.”

The NKVD officer told Tolstoy that he was being developed as the head of a large, extensive anti-Soviet conspiracy, in which many repatriates and returnee writers were to become participants. The authorities were planning a large process, scheduled for 1940-41. And its preparation was disrupted by the unexpected signing of the Peace Pact with Germany by the NKVD, when all supposedly fascist spies urgently needed to be reclassified as English and French. This, of course, was not an insurmountable obstacle for Stalin’s executioners, but it did require some time. And here in Europe the fields of the Second World War began to expand, and the defendants in the failed writers’ conspiracy in Moscow had to be expelled individually and under a different accusatory sauce.

From this whole story, my father remembered only three names spoken by Alexei Tolstoy - Sergei Efron, Pavel Tolstoy and Nadezhda Stolyarova. I immediately tried to correct him: probably not Nadezhda, but Natalya Stolyarova, who returned to Moscow from Paris in 1934, worked as a translator at the Writers' Union during visits of French writers and after the war became Ilya Ehrenburg's secretary. “Yes, she is,” the father confirmed, “but I remembered her as Nadezhda.”

So both sisters are our agents

I surprised my father by saying that Nadezhda Stolyarova also exists and that she is alive (our conversation took place in 1993), lives in Switzerland, that she is a hero of the French Resistance and the French government has provided her with a social apartment in Paris, which she rents to a Russian emigrant. And that not more than two months ago I was visiting this apartment, drinking Bordeaux and snacking on wonderful Camembert. And she really is Natalia Stolyarova’s sister.

My father looked at me carefully: “So, both sisters are our agents.”

Our conversation in 1993 was still very rudimentary and information-poor. Over the past 20 years, some realities have emerged much more clearly, and the picture seems to me to be as follows (I emphasize that this is all nothing more than a hypothetical diagram). And if the previous threads leading to the hole were, relatively speaking, horizontal, now they will be vertical.

Since at least 1921, emigrant Alexei Tolstoy had been developed by Soviet intelligence as bait for a certain part of the Russian diaspora. Ilya Erenburg and Alexander (Vladimir) Vetlugin were involved in the work on its “correct” orientation (in particular, but not only). Tolstoy, of course, himself thought about returning, but the task of the Cheka included the disintegration of the Russian emigration, and Tolstoy’s figure (jovial, quite cynical, nationally colorful and, importantly, talented) for the time being was suitable for this purpose. In Berlin, Alexei Tolstoy was worked to the fullest, quarreled with whoever was needed and discredited. His own guilt in this, his inability to distinguish good from evil, is undeniable. Now, according to the laws of hydrodynamics, a large fish returning to its homeland had to carry smaller fish with it along with the flow of water. All this happened, and in general terms it is known and described many times: Alexander Drozdov, Georgy Venus, Ivan Sokolov-Mikitov, Ilya Vasilevsky (Not-Letter) and a number of other writers repatriated.

But this turned out to be only the first stage of a large and long special operation. Alexei Tolstoy, who had fallen into the net, began to be adapted at a new stage for the next moves. Only a seer or a madman could speculate that the Bolshevik revolution would begin to devour its children in a decade. But it was clear even to an infant that power would benefit incredibly from Tolstoy’s return.

One of the roles destined for the writer is the participation of the red count in what I would call the “patriotic NEP.” Patriotic NEP is a propaganda myth that includes speculation on the concepts of statehood, traditional values, the fight against leftist trends in culture, economic growth, and the revival of historical names.

Nothing could be checked from abroad

The right flank and the political center of emigration were strongly impressed by the strengthening of state demagogic discourse in the USSR in the political economic field (“the Bolsheviks are working to strengthen the state”). In the capitals of the Russian diaspora, the marked statistical data published in Soviet publications was seriously discussed. The industrial success of the proletarian state turned naive European heads. Nothing could be checked from abroad.

And the transition from state to sovereign was quite logical: the appearance of Tolstoy’s novel “Peter the Great” made the most positive impression on the monarchists in exile. Before the war, the GPU-NKVD, of all the emigration, feared the monarchists most of all. Agitprop became convinced that with the appearance of the novel about Peter, the value idea (patriotic NEP) was found correctly. History, which had been grossly supplanted by social studies in the 1920s, was returned to school curricula. It was even decided to curtail and crumple up some political trials - for example, the so-called Academic Case, the trial of historians Sergei Platonov, Evgeniy Tarle and others. For the first time since pre-revolutionary times, Vasily Klyuchevsky’s “Course of Russian History” was published (in mass circulation).

In propaganda terms, this was a serious victory, the significance of which can be judged by the fact that hundreds of emigrants by the mid-1930s asked permission to return to their homeland.

It was for this delicate area - persuading emigrants to return - that Alexey Tolstoy was needed.

The activities of Sergei Efron (the head of the Parisian “Union of Return”, closely and secretly associated with Alexei Tolstoy in the mid-30s) were carried out precisely under this “sauce”, and Alexei Tolstoy played one of the first violins in this entire KGB-agitprop war.

But the one who was entrusted with delicate secrets under Stalin, after a while, as a rule, became a target. The dossier on Alexei Tolstoy was growing. The show trial of a group of repatriates (it is possible that with the prosecutorial participation of Andrei Vyshinsky) was supposed to reveal the sinister role of the writer in the creation of an international spy network. What he was assigned to do abroad was what he should have been judged for. Well known practice.

Literary critic Yuri Oklyansky in his 2009 book “The Dissolute Classic and the Centaur: Alexei Tolstoy and Pyotr Kapitsa. The English Trace” raised the long-overdue topic of impending repressions. Oklyansky did not work with archives; his construction is based on published memoirs and recorded conversations with contemporaries of the events. This is probably why Oklyansky’s correctly posed question is shifted to 1944 and is essentially based on the idea of an English spy trail. Oklyansky became aware of this idea from the memoirs of Cornelius Zelinsky, published in 1989 (magazine “Questions of Literature”, No. 6), where, according to Alexander Fadeev, a conversation with Stalin is reproduced. The idea of “Alexey Tolstoy – an English spy” was put forward, or rather, it was Stalin who voiced it.

Didn't you know that Alexei Tolstoy was an English spy?

Here is Fadeev’s story as recorded by Zelinsky: “Why should I tell you the names of these spies when you were obliged to know them? But if you are such a weak person, Comrade Fadeev, then I will tell you in which direction to look and how you should help us. Firstly, a major spy is your closest friend Pavlenko. Secondly, you know very well that Ilya Ehrenburg is an international spy. And finally, thirdly, didn’t you know that Alexey Tolstoy was an English spy? Why, I ask you, were you silent about this? Why didn’t you give us a single signal?”

Oklyansky, already on his own, builds a possible English arc, discussing how the accusation could go: Ilya Erenburg, Pyotr Pavlenko, Pyotr Kapitsa, H.G. Wells, Mura Budberg are trying on the role of accomplices here.

All this is quite plausible, and I do not reject Oklyansky’s construction at all. But all these are names for the post-war case (or the case of the last months of the war). An NKVD official unknown to us spoke with Alexei Tolstoy back in 1943, and it was specifically about the pre-war dossier.

Published investigative materials on other arrested writers show that the name of Alexei Tolstoy appears there constantly. These are protocols of interrogations of Mikhail Koltsov, Sergei Efron, Vsevolod Meyerhold, Isaac Babel and other arrested people. At first, during the first interrogations, before the torture began, Tolstoy was characterized as an acquaintance, a guest or owner of the house, an interlocutor who was not involved and did not lure him into any criminal activity. Then (probably after using “illegal investigative methods”) the assessment changes: he is a spy, an agent, and an organizer of secret meetings under the guise of a hospitable dinner, and so on.

It is well known what role salons played everywhere and at all times for intelligence purposes.

The first documents in Tolstoy's personal file appeared, undoubtedly, no later than 1921, when Tolstoy was taken into development in Paris. Work in the Berlin newspaper "Nakanune", the creation of a group of writers around the Literary supplement to this newspaper (Tolstoy is the editor-in-chief of the supplement), trips to Europe in the 30s, the constant reception of visiting foreigners in his home... It is well known what the role of intelligence agencies is purposes everywhere and at all times salons played. Tolstoy's open house was used one hundred percent by the GPU-NKVD from the very first day of his return to his homeland.

So, what should have been blamed on the writer in the late 30s and early 40s during the trial of the emigrant conspiracy? The answer, it seems to me, is in the very list of those writers whom Tolstoy should have persuaded to return to Russia. Or take an active part in the return, play a mediating role.

This is, firstly, Alexander Kuprin, who in 1937 no longer really understood where he was being taken and what he agreed to. Alexander Ivanovich’s propaganda contribution turned out to be shallow, but there were natural senile and alcoholic reasons for this. However, Tolstoy’s role in luring Kuprin to Moscow has long been identified, although it has not been analyzed by historians due to recent archival restrictions.

In his personal “list of atrocities” Tsvetaeva’s name cannot be crossed out

This is Marina Tsvetaeva, whom Tolstoy persuaded to return in 1935 during the Writers' Congress for Cultural Freedom, held in Paris. Marina Ivanovna, as you know, did not return because of Tolstoy, however, her name cannot be crossed out in his personal “list of atrocities”.

This is Evgeny Zamyatin, with whom Alexey Nikolaevich maintained written and personal contact throughout the 30s. Zamyatin’s case is extremely complex and mysterious. What goal did the Soviet elite pursue by releasing him to Europe? Not for philanthropic reasons. To what extent was the script developed for him, and what part of it did Zamyatin carry out? The connection between Tolstoy and Zamyatin was constantly maintained: letters from Evgeniy Ivanovich to Leningrad are known, as well as correspondence between Zamyatin’s wife and Tolstoy’s wife, Natalya Krandievskaya, including after Zamyatin’s death. And even if this is considered an innocent table joke, then this joke is recorded on paper: Alexei Tolstoy was going to marry his daughter Maryana to Zamyatin in 1937.

Guyana went to work at a pasta factory, where her finger was torn off by a machine.

This is the daughter of Mother Maria Guyana, with whom Alexey Tolstoy played Soviet happiness in the most irresponsible way and whom he quickly abandoned. Gayana was brought from Paris in 1935, settled in a Tolstoy family in Detskoye Selo (the city of Pushkin), she went to work at a pasta factory, where her finger was torn off by a machine (she reassured her mother in letters: just a piece of phalanx), and soon Tolstoy began to get a divorce with his wife (Natalia Krandievskaya), and everyone no longer cared about Guyana.

But another returnee was assigned to Guyana - a distant relative Pavel Tolstoy, another resident of the orphanage, who was instantly recruited by the Leningrad security officers and wrote denunciations against the benefactor himself, Alexei Nikolaevich. He tried to involve my father, Nikita Alekseevich, in an underground anti-Soviet organization, but his father cleverly beat him. A few years later, Pavel Tolstoy became one of the main witnesses for the prosecution in the case of Sergei Efron, which did not prevent him from sharing Efron’s fate.

Finally, there is Ivan Bunin, about whom there is even Tolstoy’s letter to Stalin in 1940: Alexei Nikolaevich emphasizes Bunin’s services to Russian literature. Where should we fit this intercession before the most famous emigrant and Nobel laureate? According to the rules of that era, this could not be a personal initiative. Tolstoy could only be the executor of a subtle plan.

Some did not live to see the ready-made dock, some did not take Tolstoy’s bait, but the voluminous dossier that was accumulating on the writer should, it seems to me, contain these names.

Let me remind you that in a conversation with his son (in the fall of 1944), Alexei Tolstoy also named Sergei Efron and Natalya Stolyarova. Stolyarova returned back in 1934 and not in connection with Alexei Tolstoy. The story of Sergei Efron's hasty return is well known.

The extent to which the investigators' plans changed depending on the orders of their superiors can be judged by the tragicomic episode with the arrested Dmitry Svyatopolk-Mirsky. Svyatopolk-Mirsky was arrested in the summer of 1937. He received eight years in a Magadan camp, where he died two years later. Fate sent him greetings from beyond the grave: the NKVD needed to strengthen the charges against Sergei Efron and urgently requested the Magadan prisoner to Moscow. Beria approved this move. But Dmitry Petrovich was no longer alive. This means that in 1937 and 1938 there was no need for a conspiracy yet.

Did Tolstoy complete a secret mission? Partly yes. The failure was partly attributed to a sudden change in the political context - the Peace Pact with Hitler. And then - war.

In 1944, in a personal conversation with Fadeev, Stalin named Alexei Tolstoy as a long-time English spy. Apparently, Tolstoy passed away on time. But Stalin still had a grudge against him. Is this why no one from the state came to his funeral in February 1945 except Andrei Yanuaryevich Vyshinsky (probably to say goodbye to his escaped client) and the eternal Shvernik?

Personal life

The writer was called a ladies' man and a bon vivant. There were four marriages in the life of Alexei Tolstoy. The first is with Yulia Rozhanskaya, the daughter of a college adviser. The writer met a girl in Samara, at a rehearsal for a play in an amateur theater. In 1901, after spending the summer together at the Rozhansky dacha, Tolstoy persuaded Yulia to leave for St. Petersburg, where she entered medical school. The following year the couple got married, and in January 1903 their son Yuri was born (died 1908).

Alexei Tolstoy with his wife Yulia Rozhanskaya

During the revolutionary events, Alexey Tolstoy went to Germany, where he met the artist Sofia Dymshits. He officially separated from his first wife in 1910. The Jewish woman Sophia converted to Orthodoxy and married Tolstoy. In 1911, daughter Marianna was born.

Alexey Tolstoy with his wife Lyudmila Krestinskaya-Barsheva

Soon the loving writer drew attention to the poetess Natalya Krandievskaya and left his second wife. In 1914, Tolstoy and Krandievskaya got married, the marriage lasted until 1935. In union with Natalya Vasilyevna, who became the prototype of Katya from “Walking Through Torment,” sons Nikita and Dmitry were born.

In August 1935, the beautiful secretary Lyudmila Krestinskaya-Barsheva came to the Tolstoys’ house. In October, Lyudmila, who was strikingly younger than Alexei Nikolaevich, became his wife. They lived together until the death of the writer.

Creativity[ | ]

In the trilogy “Walking in Torment” (1922-1941), he tried to present Bolshevism as rooted in national and popular soil, and the revolution of 1917 as the highest truth comprehended by the Russian intelligentsia.

The historical novel "Peter I" (books 1-3, 1929-1945, unfinished) - perhaps the most famous example of this genre in Soviet literature, contains an apology for the strong and cruel reformist government.

Tolstoy's novels "Aelita" (1922-1923) and "Engineer Garin's Hyperboloid" (1925-1927) became classics of Soviet science fiction.

The story “Bread” (1937), dedicated to the defense of Tsaritsyn during the civil war, is interesting because in a fascinating artistic form it tells the vision of the civil war in Russia that existed in the circle of I.V. Stalin and his associates and served as the basis for the creation of Stalin cult of personality. At the same time, the story pays detailed attention to the description of the warring parties, the life and psychology of the people of that time.

Other works include the story “Russian Character” (1944), the play “Conspiracy of the Empress” (1925, together with P. E. Shchegolev). Tolstoy is one of the alleged authors of the forged "Diary of Vyrubova" (1927). Popular legend attributes to him (without any reason) the authorship of the anonymous pornographic story “Bathhouse”[19].

The author subjected some major works to serious revision in Soviet times - the novels “Sisters”, “Hyperboloid of Engineer Garin”, “Emigrants” (“Black Gold”), the play “Love is a Golden Book” and others.

Death

In 1944, doctors gave Alexei Tolstoy a terrible diagnosis: rapidly progressing lung cancer. For six months the writer was tormented by hellish pain. He died in February 1945 in Moscow, before the Victory.

Alexei Tolstoy's grave

Alexei Tolstoy was buried at the Novodevichy cemetery, declaring state mourning.

In October 1987, a museum was opened in the capital on Spiridonovka Street, where the writer and his wife Lyudmila lived in recent years.

Quotes by Alexei Tolstoy

- This world will inevitably perish. Here only blackbirds live intelligently.

- It must be that when a person has everything, then he is truly unhappy.

- The soldiers were required to stubbornly and obediently die in those places indicated on the map.

- People cannot be left without leaders. They are drawn to get on all fours.

- Here they fought: brother against brother, father against son, godfather against godfather - that means, without fear and mercilessly.

- It is necessary that the amount of gold be limited, otherwise it will lose the smell of human sweat.