Biography of Fyodor Chaliapin

Fyodor Chaliapin is a world-famous Russian bass, chamber and opera singer. He performed as a soloist at the Bolshoi and Mariinsky theaters, and directed the latter for some time. A gifted man, he was engaged in painting and sculpture, and appeared in feature films several times. He also performed as a soloist at the Metropolitan Opera and sang at La Scala.

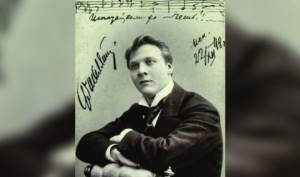

In the photo: Fyodor Chaliapin

He was awarded the Order of Noble Bukhara (Golden Star), the Golden Cross of the Prussian Eagle, and the English Order for Special Merits in Art. He received the title of the first People's Artist of the Republic in 1918. Commander of the French Legion of Honor. He left Soviet Russia in 1922, shortly after the execution of his friends from the noble Stuart family. He died at 65 from leukemia in Paris in 1938.

Childhood and youth

Fedor was born in the winter of 1873 into the family of Ivan and Evdokia Chaliapin, who lived in a working-class district of Kazan called Sukonnaya Sloboda.

The family lived in a wing of the Lisitsins’ house on Rybnoryadskaya Street. Of course, this outbuilding is long gone, but the house still stands, although this street now bears the name of Pushkin. Father, Ivan Yakovlevich, a native of the Vyatka province, a peasant. He moved to Kazan with his wife and, after years of hard physical work as janitors and water carriers, became a clerk in the zemstvo administration. Mom, Evdokia Mikhailovna, nee Prozorova, ran the house.

Father of Fyodor Chaliapin

The boy was born weak and sickly, the parents were in a hurry to baptize the baby, they were afraid that he would leave this world unbaptized. In order not to completely catch a cold in the child, the priest of the Epiphany Cathedral performed an abbreviated ceremony in a hurry and, because of the haste, entered the baby into the church register as Fyodor Shalyapkin.

The family lived poorly, and soon after Fedya’s birth they moved to the outskirts of Kazan, to the village of Ametovo. No matter how hard Ivan Yakovlevich tried to break with the village he hated, the way of life here was different from life in a working-class settlement: cold, hunger, a house with an earthen floor, dim light from a splinter, vodka and fights.

House in Ametovo, where Fyodor Chaliapin spent his childhood

Evdokia gave birth three more times, but both her daughter Evdokia and her youngest son Nikolai did not survive the scarlet fever epidemic in 1882. Son Vasily was born in 1884 and did not experience the terrible illness. Fyodor also suffered from scarlet fever, but he survived, got stronger, and grew up.

The father, having decided to attach his son to the craftsmanship, brought him to study with a shoemaker. At the same time, Fedya studied literacy and writing at a private school. One day he entered the church while an evening service was going on there. And he was amazed at how his peers sang according to the notes in the church choir. And he loved to sing, because in his circle, no business began without a song - it helped to forget about the gloomy reality. Thanks to the neighbor-regent, who heard how clearly the boy sang, he soon learned to read music and learned the basics of musical literacy. Fyodor was also taken as a singer in the temple.

The temple in which young Chaliapin sang

It was not fun at home: the father began to drink, and at first he only shouted at his mother’s reproaches, then began to beat her. The boy once rushed to her aid, but only got hit in the neck by his drunken parent. A great joy was the dumplings, which Fedya loved desperately, but which his mother made only after every twentieth, when his father brought home his salary. But more and more often he drank away his monthly earnings.

Fyodor Chaliapin in his youth (1892)

Despite the constant swearing and beatings in the house, Fedya found something to be happy about. He had friends with whom he climbed trees and roofs and made kites. In his autobiography, written thanks to Maxim Gorky, Chaliapin recalled: After elementary school, Chaliapin continued to study first at the Fourth and then at the Sixth Parish School, from which he graduated with the highest grade. For some time he worked as an assistant clerk, and then his father assigned him to be a student at a vocational school in Arsk. The teenager was quietly glad that he was leaving the gloomy area; it seemed to him that some beautiful country was waiting for him ahead.

First steps to success

Having first come to the theater for the production of “Russian Wedding,” Fyodor could no longer imagine life without a stage. And after hearing the opera “A Life for the Tsar” by Mikhail Glinka, he firmly decided to join the theater. Fyodor Chaliapin - Dark Eyes But at first he only managed to get a job as an extra in Vasily Serebryakov’s troupe, and not the first time. At the first audition for the choir, some “oinking” lanky guy got into the choir instead. A few years later, when Chaliapin met Maxim Gorky, he told him about his creative path. The writer just grinned, saying that he was that young man. But since he had no singing talent, he was quickly kicked out of the choir.

Maxim Gorky and Fyodor Chaliapin

The first performance of the future world celebrity took place in the spring of 1890. Endlessly worried, he performed the role of Zaretsky in Pyotr Tchaikovsky's opera Eugene Onegin. Fedor worked at Serebryakov’s enterprise for another three months, and then moved to Ufa.

The Ufa period began for him with small performances in the operetta troupe of Semyon Semenov-Samarsky. Over time, the talented self-taught man began to be assigned roles in plays. He gained confidence on stage and performed the roles of Ferrando in Troubadour and Unknown in Askold’s Grave. Chaliapin was noticed and invited to the Ufa zemstvo, but young Fedor chose to join the troupe of Georgy Derkach from Little Russia, which was just on tour in Ufa.

Fyodor Chaliapin in his youth

With her, the singer visited various cities of Russia, Ukraine, and Central Asia. When the troupe came to perform in Tiflis, Chaliapin met former artist of the Imperial Theater Dmitry Usatov, who offered to help him stage his voice. The gifted young man lived in the Caucasus for a year, performing bass parts on the stage of the Tiflis Opera.

Dmitry Usatov

In 1895, serious changes occurred in the singer’s creative career. He was accepted into the St. Petersburg Opera Company of the Imperial Theaters. Fyodor became famous on the Mariinsky stage for his roles as Mephistopheles in Faust by Charles Gounod and Ruslan in Ruslan and Lyudmila by Mikhail Glinka.

Autographed photo of Chaliapin

The freedom-loving Chaliapin began to be oppressed by the strictness and foundations of the theater. So when philanthropist Savva Mamontov invited him to perform in his theater, the singer agreed. In this troupe the unprecedented creative potential of the Kazan nugget was finally revealed. He does all the bass parts. In the operas “Pskovite”, “Sadko”, “Rusalka”, “Khovanshchina”, Chaliapin’s voice captivated the audience.

Biography[ | ]

Ivan Yakovlevich Shalyapin (1837-1901) - father of F.I. Shalyapin

The son of the peasant of the Vyatka province Ivan Yakovlevich Shalyapin (1837-1901), a representative of the ancient Vyatka family of the Shalyapins (Shelepins). Shalyapin's mother Evdokia Mikhailovna (nee Prozorova, 1845-1891 [Comm. 1]) was a peasant woman from the village of Dudinskaya (now Dudintsy) in the Kumen volost of the Vyatka province [14]. Ivan Yakovlevich and Evdokia Mikhailovna got married on January 27, 1863 in the Transfiguration Church in the village of Vozhgaly. As a child, Chaliapin was a singer in a church choir. As a boy, he was sent to study shoemaking with N.A. Tonkov, then with V.A. Andreev. He received his primary education at Vedernikova’s private school, then studied at the Fourth Parish School in Kazan, and later at the Sixth City Primary Two-Class School. In May 1885, Chaliapin graduated from college, receiving the highest grade. In the same year, Fyodor’s father arranged for him to become a student at the newly opened vocational school in Arsk. “I thought,” Chaliapin recalled, “that I was going to some beautiful country, and I was quietly glad that I was leaving Sukonnaya Sloboda, where life was becoming increasingly difficult for me.”[15]

Start of career[ | ]

F. Chaliapin in 1893

Chaliapin himself considered the beginning of his artistic career to be 1889, when he entered the drama troupe of V. B. Serebryakov as an extra. On March 29, 1890, Chaliapin’s first performance took place - he performed the part of Zaretsky in P. I. Tchaikovsky’s opera “Eugene Onegin” staged by the Kazan Society of Performing Art Lovers. Throughout May and early June 1890, Chaliapin was a chorus member of V. B. Serebryakov’s operetta company.

On September 19, 1890, Chaliapin moved from Kazan to Ufa and began working in the choir of an operetta troupe under the direction of S. Ya. Semenov-Samarsky. He received the solo part of Stolnik in Moniuszko's opera "Pebble", replacing the artist who accidentally fell ill. This debut brought out the 17-year-old Chaliapin, who was occasionally assigned small opera roles, for example, Ferrando in Il Trovatore. Once Chaliapin fell on stage, sitting past a chair - since then, all his life he vigilantly watched the chairs on the stage, fearing to miss again.

Chaliapin and Sergei Rachmaninov, early 1890s

The following year, Chaliapin performed as the Unknown in Verstovsky's Askold's Grave. He was offered a place in the Ufa zemstvo, but the aspiring singer joined the Ukrainian troupe of G. I. Derkach that arrived in Ufa. Traveling with her led him to Tiflis, where he was able to take his voice seriously for the first time, thanks to the singer Dmitry Usatov. Usatov not only approved of Chaliapin’s voice, but, due to the latter’s lack of financial resources, began giving him singing lessons for free and generally took a great part in his life. He also arranged for Chaliapin to perform in the Tiflis opera of Ludwig-Forcatti and Lyubimov. Chaliapin lived in Tiflis for a year, performing the first bass parts in the opera.

In 1893 he moved to Moscow, and in 1894 to St. Petersburg, where he sang in Arcadia in Lentovsky's opera troupe. In the winter of 1894-1895, Chaliapin performed in an opera company at the Panaevsky Theater, in Zazulin's troupe. The beautiful voice of the aspiring artist and especially his expressive musical recitation, together with his truthful playing, attracted the attention of critics and the public to him. In 1895, Chaliapin was accepted by the directorate of the Imperial Theaters into the St. Petersburg Opera Troupe. On the stage of the Mariinsky Theater he successfully sang the roles of Mephistopheles (Faust by C. Gounod) and Ruslan (Ruslan and Lyudmila by M. I. Glinka). Chaliapin’s varied talent was also expressed in D. Cimarosa’s comic opera “The Secret Marriage,” but was not properly appreciated. In the 1895-1896 season, he “appeared quite rarely and, moreover, in parties that were not suitable for him.”

Mamontov Opera[ | ]

The philanthropist S.I. Mamontov, who at that time ran an opera house in Moscow, noticed Chaliapin’s outstanding talent and persuaded him to join his troupe. Chaliapin sang in Mamontov’s “Private Russian Opera” in 1896-1899, and during these four seasons he gained great fame. Here he developed artistically and developed his stage talent, performing a number of solo roles. Thanks to his subtle understanding of Russian music in general and modern music in particular, he individually and deeply truthfully created a number of significant images in such works of Russian composers as “The Woman of Pskov” ( Ivan the Terrible

), “Sadko” (

The Varangian Guest

) and “Mozart and Salieri” (

Salieri

) by N. A. Rimsky-Korsakov;

“Mermaid” ( Melnik

) by A. S. Dargomyzhsky;

“Life for the Tsar” ( Ivan Susanin

) by M. I. Glinka;

"Boris Godunov" ( Boris Godunov

) and "Khovanshchina" (

Dosifei

) by M. P. Mussorgsky. At the same time, he also worked on roles in foreign operas; Thus, the role of Mephistopheles in C. Gounod’s opera “Faust” received bright, strong and original coverage in his broadcast.

Mamontov, giving Chaliapin carte blanche, helped the singer to reveal his talent. Chaliapin himself later recalled[16]:

S.I. Mamontov told me:

- Fedenka, you can do whatever you want in this theater! If you need costumes, tell me and there will be costumes. If we need to stage a new opera, we’ll stage an opera! All this dressed my soul in festive clothes, and for the first time in my life I felt free, strong, capable of conquering all obstacles.

In his autobiographical book “Mask and Soul,” Chaliapin characterizes these years of his creative life as the most important: “From Mamontov I received the repertoire that gave me the opportunity to develop all the main features of my artistic nature, my temperament.”

The flourishing of creativity[ | ]

A. I. Kuprin and F. I. Shalyapin.

Petersburg. 1911 Chaliapin in the image of Mephistopheles (photo by S. M. Prokudin-Gorsky, 1915) F. I. Chaliapin with his family in a military hospital during the First World War, 1915 “Hey, let’s whoop” performed by Fyodor Chaliapin, 1902 “Dubinushka” "(words by A. Olkhin) performed by Fyodor Chaliapin, until 1917 "Because of the island to the core" performed by Fyodor Chaliapin, until 1938 In 1899, Chaliapin again entered the service of the Imperial Theaters - this time he sang in Moscow , at the Bolshoi Theater, where he enjoyed enormous success. Chaliapin's tour performances on the imperial Mariinsky stage constituted a kind of event in the St. Petersburg musical world.

In 1901, Chaliapin gave 10 performances at Milan's La Scala theater: his performance in the title role in A. Boito's opera "Mephistopheles" was highly praised.

During the revolution of 1905, he donated proceeds from his performances to workers. His performances with folk songs (“Dubinushka” and others) sometimes turned into political demonstrations. In 1907-1908 he toured in the USA and Argentina.

Since 1914, he performed in the private opera companies of S. I. Zimin in Moscow and A. R. Aksarin in Petrograd.

In 1915, Chaliapin made his film debut, he played the role of Ivan the Terrible in the historical film drama “Tsar Ivan Vasilyevich the Terrible” (based on the drama “The Pskov Woman” by Lev Mei).

In 1917, during the production of G. Verdi’s opera “Don Carlos” at the Bolshoi Theater, Chaliapin performed not only as a singer, performing the part of Philip, but also as a director. His next directorial experience was the production of A. S. Dargomyzhsky’s opera “Rusalka”. He chooses the young singer K. G. Derzhinskaya for the main role[17].

During the First World War, the singer opened two hospitals for wounded soldiers with his own funds, without notifying the public about his charity. Lawyer M. F. Volkenstein (he handled Chaliapin’s financial affairs for many years) recalled: “If only they knew how much Chaliapin’s money passed through my hands to help those who needed it!”[18][ unauthorized source?

][19].

Revolutionary period[ | ]

Chaliapin and Maxim Gorky at the presidium of the ceremonial meeting dedicated to the celebration of May 1 in Petrograd (1920).

Since 1918, Chaliapin has been the artistic director of the former Mariinsky Theater. In the same year, he was the first to receive the title of People's Artist of the Republic.

In exile[ | ]

Since July 1922[20], Chaliapin has been on tour abroad, in particular in the USA, where his American impresario was Solomon Yurok. The singer left with his second wife, Maria Valentinovna. His long absence aroused suspicion and negative attitudes in Soviet Russia; Thus, in 1926, V.V. Mayakovsky wrote in his “Letter to Gorky”[21]:

Or live for you how Chaliapin lives,

splashed with scented applause?

Come back Now such an artist

back to Russian rubles -

I'll be the first to shout: - Roll back,

People's Artist of the Republic!

In 1927, Chaliapin donated the proceeds from one of his concerts to the children of emigrants, which was presented on May 31, 1927 in the VSERABIS magazine by a certain S. Simon as support for the White Guards[22]. This story was written in detail in Chaliapin’s autobiography “Mask and Soul”[23]. On August 24, 1927, by a resolution of the Council of People's Commissars of the RSFSR, he was deprived of the title of People's Artist and the right to return to the USSR. This decision was justified by the fact that he did not want to “return to Russia and serve the people whose title of artist was awarded to him” or, according to other sources, by the fact that he allegedly donated money to monarchist emigrants.

“Proposals to posthumously restore the title of People's Artist of the Republic to F. I. Chaliapin” were considered by the Central Committee of the CPSU and the Supreme Council of the RSFSR in 1956, but were not accepted. The 1927 decree was repealed 63 years after the singer's death. On June 10, 1991, the Council of Ministers of the RSFSR adopted Resolution No. 317, prescribing

Cancel the resolution of the Council of People's Commissars of the RSFSR dated August 24, 1927 “On depriving F. I. Chaliapin of the title “People’s Artist”” as unfounded.

At the end of the summer of 1932, Chaliapin starred in films, playing the main role in Georg Pabst’s film “The Adventures of Don Quixote” based on the novel of the same name by Cervantes. The film was shot in two languages at once - English and French, with two casts. The music for the film was written by Jacques Ibert, and location shooting took place near Nice. In 1935-1936, Chaliapin, together with accompanist Georges de Godzinsky, went on his last tour - to the Far East. He gave 57 concerts in Manchuria, China and Japan.

In the spring of 1937, Chaliapin was diagnosed with leukemia. On April 12, 1938, at the age of 66, he died in Paris in the arms of his wife. On April 14, the Izvestia newspaper published an obituary signed by Mark Reisen:

The telegraph brought news of the death of Fyodor Chaliapin in Paris.

Chaliapin, having gone through a long creative path in his time, created a number of images that went down in the history of the Russian opera theater.

However, in the prime of his strength and talent, Chaliapin betrayed his people, exchanged his homeland for a long ruble. Having been cut off from his native soil, from the country that raised him. Chaliapin did not create a single new role during his stay abroad. All his performances abroad were random. Chaliapin's enormous talent dried up long ago.

He passed away without leaving anything behind, without passing on his work methods or much experience to anyone. Chaliapin's literary heritage does not represent anything interesting for art. This is a chronological presentation of various episodes, striking in its ideological squalor.

— “Izvestia”, No. 87 from 04/14/1938

He was buried in the Batignolles cemetery in Paris (25th Division). The inscription on the gravestone reads: “Here lies Fyodor Chaliapin, the brilliant son of the Russian land.” After negotiations with Baron Eduard von Falz-Fein and the Soviet writer Yulian Semyonov, Fyodor Fedorovich Chaliapin allowed the transfer of his father’s ashes from France to Russia, which was announced on December 24, 1982 in Vaduz, at the residence of Baron Eduard Falz-Fein, in the presence of the owner and Yulian Semyonov a corresponding document has been drawn up[24]. After the death of Fyodor Fedorovich, the baron bought the Chaliapin family heirlooms, which remained in Rome, and donated them to the Chaliapin House Museum in St. Petersburg. The reburial ceremony took place at the Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow on October 29, 1984, without the participation of Falz-Fein. Two years later, a tombstone by sculptor A. Yeletsky and architect Yu. Voskresensky was installed there.

Career development and emigration

At the turn of the century, Fyodor Ivanovich became a soloist of the Bolshoi Theater. The stunning success with the public and critics made the singer a people's favorite. One of the critics wrote that now there are three miracles in the capital: the Tsar Cannon, the Tsar Bell and the Tsar Bass of Chaliapin.

Chaliapin in Faust

In 1901, the famous bass gave ten performances on the stage of La Scala in Milan. Mephistopheles in his performance was recognized by the demanding homeland of opera as a standard of the highest skill.

Soon Chaliapin conquered America and Argentina. Thanks to his talent, the whole world recognized Russian composers and the famous arias of Ivan the Terrible, Melnik, Ivan Susanin, Varangian Guest, Boris Godunov.

Chaliapin as Boris Godunov

The First World War interrupted the singer's tours. He performed in Moscow and Petrograd, and in 1915 he starred in films, playing the Tsar in the historical drama “Tsar Ivan Vasilyevich the Terrible” by Alexander Ivanov-Gai. For Russian soldiers wounded in the war, he opened two hospitals at his own expense, but the general public knew nothing about it.

Fyodor Chaliapin and Alexander Kuprin (1911)

The year 1917 was not only a year of revolution for Chaliapin, but also a creative breakthrough: on the stage of the Bolshoi Theater he staged Giuseppe Verdi's opera Don Carlos, and then Alexander Dargomyzhsky's opera The Mermaid. In 1918, Fyodor Ivanovich again went to the city on the Neva to head the Mariinsky Theater on instructions from the revolutionary committee. At the same time he was awarded the title of People's Artist.

Chaliapin headed the Mariinsky Theater

Since January 1920, Fedor had plans to escape abroad. The reason was the execution by the new government of his close friends, the Stuart barons. Chaliapin understood that he could suffer the same fate. His house was regularly searched. There was also less work. Not only Chaliapin, but all pre-revolutionary artists. Once, all the props at the Mariinsky Theater were almost taken away in favor of provincial “proletarian” theaters. Chaliapin had to go to Vladimir Lenin and persuade him to stop the barbaric theft.

Fyodor Chaliapin – Olofren

Until 1921, Chaliapin was barred from going on tour to “enemy capitalist” countries. Finally, he was released on tour to Tallinn, which the artist himself, out of old habit, called Revel. After this there was a concert in Riga, where Fedor was given a lucrative offer to tour the USA and Europe.

Chaliapin among European fans

Fyodor could have stayed in Europe even then, but his family remained in his homeland, without which he could not imagine life. He returned to St. Petersburg and asked for permission to perform abroad with his family, emphasizing that his performances make excellent advertisement for the Land of the Soviets - after all, he is a wonderful artist, and it is not his fault that he was born long before the era of Bolshevism. And permission was received. Only the singer’s eldest daughter remained in Moscow. The rest of the family emigrated with Chaliapin to Paris. Fedor returned to the USSR many years after his death - to be buried at the Novodevichy cemetery.

Notes[ | ]

- ↑ 1 2 Riemann G.

Chaliapin //

Musical Dictionary

:

Translation from the 5th German edition

/ ed. Yu. D. Engel, trans. B. P. Yurgenson - M.: Musical Publishing House of P. I. Yurgenson, 1901. - T. 3. - P. 1412-1413. - Internet Movie Database (English) - 1990.

- ↑ 12

Feodor Ivanovich Chaliapin - ↑ 123

Archivio Storico Ricordi - 1808. - Archive of Fine Arts - 2003.

- Bibliothèque nationale de France

BNF identifier (French): open data platform - 2011. - Feodor Chaliapin // Encyclopædia Britannica (English)

- 2GIS - 1999.

- Elena Borisova.

Fyodor Chaliapin: little-known facts and milestones of creativity

(unspecified)

. aif.ru (February 13, 2013). Date accessed: September 20, 2019. - Resolution of the Council of Ministers of the RSFSR dated June 10, 1991 No. 317 (unspecified)

(inaccessible link). Date accessed: September 20, 2021. Archived September 28, 2021. - Shalyapin F.I.

- article from the Great Soviet Encyclopedia. - ↑ 1 2 Shalyapin F.I.

// Brief musical dictionary - Sadyrin, 1998, p. 44.

- Sadyrin, 1998, p. 43-44.

- Chaliapin's places in Kazan. First publication (unspecified)

. Kazan stories. Date accessed: February 2, 2021. - Shalyapin F.I. Pages from my life: Autobiography. L.: Priboy, 1926. - P. 200

- E. Grosheva, K. G. Derzhinskaya. State Musical Publishing House, M. 1952, p. 42, 43.

- Interesting facts about Chaliapin (unspecified)

(inaccessible link).

Facts website

. Date accessed: August 30, 2021. Archived October 30, 2016. - Dmitrievskaya, Dmitrievsky, 1986, p. 140.

- Lib.ru/Classics: Chaliapin Fedor Ivanovich. Mask and soul (undefined)

. az.lib.ru. Date accessed: September 20, 2021. - Letter from the writer Vladimir Vladimirovich Mayakovsky to the writer Alexei Maksimovich Gorky (Mayakovsky) (unspecified)

. Wikisource. Access date: July 14, 2021. - The honor of Fyodor Chaliapin is now protected // Izvestia, No. 140, 06/13/1991.

- ↑ 12

Shalyapin, 1990, p. 130. - Fyodor Fedorovich Chaliapin, Yulian Semenov, Eduard Falz-Fein while F. F. Chaliapin wrote permission to transfer the ashes of F. I. Chaliapin to Moscow. Villa “Askania Nova”, Vaduz, Liechtenstein: December 22-24, 1982: [selection of photographs] / photo by Y. Semenov, E. Falz-Fein. — 1982.

- Pavel Maksimovich Zhuravlenko on M. Malkov’s website.

- Titta Ruffo, Caruso and Chaliapin (unspecified)

. nataliamalkova61.narod.ru. Date accessed: June 7, 2021. - Moshentseva, 2012.

- L'eroe della Rivoluzione d'ottobre che scelse Monza per amore (e poi tradì tutti)

- Iola Ignatievna left the USSR for Rome in the late 1950s at the invitation of her son Fyodor.

- Moscow graves. Shalyapina T. F. (undefined)

. moscow-tombs.ru. Date accessed: June 7, 2021. - K. Lasko.

Chaliapin's daughter // Soviet Culture. - 1970. - March 7. — P. 3. - At the age of 98, the daughter of Fyodor Chaliapin (unspecified)

. www.tvkultura.ru. Date accessed: June 7, 2021. - The daughter of Fyodor Chaliapin died in Rome (inaccessible link since 06/07/2017 [1508 days]).

- 3rd Zachatievsky Lane, 3. Chaliapin's House (unspecified)

(inaccessible link). moskva.kotoroy.net. Access date: June 7, 2017. Archived October 11, 2014. - Moscow City Heritage wants to seize the house in which Chaliapin lived from the owner, RIA Real Estate

(September 6, 2013). Retrieved June 7, 2021. - ↑ 12345

Dacha of F.I. Shalyapin (rest house “Poroshino”) // Code of monuments of architecture and monumental art of Russia: Ivanovo region, part 3 / resp. ed. E. G. Shcheboleva. - M.: Nauka, 2000. - P. 100-101. — 813 p. — ISBN 5-02-011595-9. - “Plyossky Bulletin” May 25 - 31, 2012, No. 21 (22), p. 8 / “Theatrical Plyos”

- Oinas D. B.

Shalyapin F. I. in Ples. Legends and facts // Materials of the scientific conference V Pless Readings. (1994). - Plyos, 2001. - pp. 74-82. - State Archive of the Ivanovo Region. F. R-2. Op. 1. D. 404

- Vyatka-on-the-network. News: A monument to Fyodor Chaliapin was unveiled in Kirov

- Federal information address system (undefined)

. fias.nalog.ru. Date accessed: June 7, 2021. Archived April 21, 2015. - Novodevichy Cemetery - Chaliapin Fedor Ivanovich (unspecified)

. devichka.ru. Date accessed: June 7, 2021. - International Opera Festival named after Fyodor Ivanovich Chaliapin (unspecified)

(inaccessible link). www.kazan-opera.ru. Date accessed: June 7, 2017. Archived May 14, 2021. - Gramophone Hall of Fame. Gramophone. Date accessed: January 2, 2021.

- A monument to Fyodor Chaliapin was unveiled in Plyos

. TASS (September 14, 2020). Date accessed: September 16, 2021.

Personal life of Fyodor Chaliapin

In his autobiography, Chaliapin admitted that in his youth he was an amorous person and often had affairs.

He first married the Italian ballerina Iola Tornaghi, whom he met at the Savva Mamontov Theater. At first, she was wary of the assertive guy who communicated with her mainly through gestures. But when she got sick and came down with a fever, and he fed the girl chicken broth, she began to treat Chaliapin with warmth.

Fyodor Chaliapin and Iola Tornaghi

He proposed to her in a very original way, singing in his inimitable bass voice from the stage during the performance of “Eugene Onegin”: “Onegin, I swear on my sword, I love Tornagi madly.” As you know, Gremin’s aria spoke of love for Tatyana. Although Iola still knew little Russian, she understood the confession of Fyodor who was in love with her and agreed to become his wife.

Iola Tornaghi with children

Over the years of their marriage, they had six children. Chaliapin learned about the birth of twins - son Fyodor and daughter Tatyana, when he was in the village of Otradnoye on the banks of the Volga. An eyewitness to how Fyodor received a telegram at the post office described this event as follows: But the large family did not restrain Chaliapin. He often went on tour to Petrograd and there he fell in love with Maria Petzold, who at that time was also not free. After some time, she divorced her husband, took her two children and began to live with her new lover. Chaliapin remained in the status of Iola’s husband.

Chaliapin's second wife Maria Petzold

In his second family, the artist had three more daughters. Fyodor Ivanovich moved to Paris with them and Maria in 1922, and then four children from Tornaga went to him (son Igor died at the age of four, and the eldest daughter Irina decided to leave in her homeland). Iola Ignatievna remained in the USSR until 1960, then moved to Rome, and in the house where she lived with Chaliapin, a museum was created at her personal request to Ekaterina Furtseva. Fyodor Chaliapin – Dubinushka

Death and memory

The legendary bass went on his last tour in 1935. Almost sixty Chaliapin concerts were held in the cities of Manchuria, China, and Japan. In 1937, Fyodor Ivanovich felt unwell and went to the hospital for examination. Blood leukemia. A year later, Chaliapin died in a Paris apartment in the arms of his wife. He was buried in the Botignolles cemetery in Paris. There is a succinct inscription on the monument: “Here lies Fyodor Chaliapin, the brilliant son of the Russian land.”

Fyodor Chaliapin with his son and wife in 1935

In 1984, his son Fyodor, with the help of writer Yulian Semenov, petitioned the Soviet leadership to rebury his father’s ashes in the USSR. Since then, Fyodor Ivanovich’s grave has been located at the Novodevichy cemetery in Moscow.

The grave of Fyodor Chaliapin

After the death of the operatic genius, some historians began to conduct their own investigations, consulting with doctors. Evidence has emerged that Chaliapin could have been poisoned with radioactive isotopes or phenol during his last tour. Kazan local historian Rovel Kashapov tried to prove that with such powerful health as Chaliapin had, blood cancer occurs in isolated cases. In addition, in 1932, Fyodor Ivanovich published the book “Mask and Soul” in Paris, where he spoke harshly about Bolshevism, Soviet power and Joseph Stalin. Allegedly, the “leader of the peoples” could not forgive him for this. Fyodor Chaliapin. How the idols left The Motherland, which the great genius loved and glorified so much, returned to him the title of the first People's Artist only in 1991. Two house museums were created in his honor in St. Petersburg and Moscow. There are monuments to him in Kazan, Ufa, the Russian capital. The name of the legendary bass is immortalized with a personal star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. An opera festival named after Chaliapin was organized in the city of Chaliapin’s childhood. In the fall of 2021, a monument to Fyodor Ivanovich was erected in Plyos, the city where Chaliapin loved to vacation.

Memory[ | ]

Monument to F.I. Chaliapin in Kazan near the hotel of the same name

- House-Museum of F.I. Chaliapin in St. Petersburg.

- House-museum of F.I. Chaliapin in Moscow.

- Chaliapin House-Museum in Kislovodsk.

- Museum A.M. Gorky and F.I. Chaliapin in Kazan.

- In August 2014, a monument to Chaliapin was erected in Kirov[40].

- In the homeland of the singer’s parents in the village of Vozhgaly, a children’s art school is named after F.I. Chaliapin, on the basis of which Chaliapin evenings are regularly held. Fyodor Ivanovich himself came to Vozhgaly to visit his sick father and donated money for the construction of the People’s House in the village.

- As of 2013, in Russia 17 streets, 2 lanes and a village in the Ivanovo region are named after Chaliapin[41].

- Kazakhstan: In Almaty there is Shalyapin Street.

- Shalyapin Street in the city of Rudny (Kustanay region) [ source not specified 1411 days

]

- In Kharkov there is Shalyapin Street.

Fyodor Chaliapin's star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame

- The name of Fyodor Ivanovich Chaliapin is immortalized with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame for his contribution to the recording industry.

- On August 29, 1999, a monument to Chaliapin was erected in Kazan, near the bell tower of the Epiphany Cathedral, in which he was baptized on February 2, 1873 (sculptor A. Balashov).

- On October 31, 1986, the opening of the tombstone monument to F. I. Shalyapin took place (sculptor - A. Eletsky, architect - Yu. Voskresensky)[42].

- On February 8, 1982, the first opera festival named after him opened in Kazan, the homeland of Fyodor Chaliapin. The festival is held on the stage of the Tatar State Opera and Ballet Theater named after. M. Jalil and since 1991 has had the status of International[43].

- The four-deck river motor ship of Project 92-016 bears the name of Fyodor Chaliapin.

- Since 1973, in the USSR, the turboprop was named after the singer.

- In Nizhny Novgorod there is a museum of F.I. Chaliapin.

- Inducted into the Gramophone Magazine Hall of Fame[44].

- In September 2021, a monument to Fyodor Chaliapin was unveiled in Plyos[45].

Film incarnations[ | ]

- Nikolai Okhlopkov (“Yakov Sverdlov”, 1940)

- Alexander Ognivtsev (Rimsky-Korsakov, 1953)

- Victor Stepanov (“Under the sign of Scorpio”, 1996)

- Alexander Blok (“His Majesty’s Secret Service”, 2006)

- Alexander Klyukvin (“Peter Leshchenko. Everything that happened...”, 2013)

- Ildar Abdrazakov (“Yolki 1914”, 2014)

- Alexander Bobrovsky (“Orlova and Alexandrov”, 2014)

- In 2002, a feature film based on the memoirs of F. Chaliapin “Mask and Soul” was released. The text from the author was read by Vladimir Simonov