early years

On September 21, 1895, in the village of Konstantinovo, Ryazan province, Sergei Aleksandrovich Yesenin, an outstanding Russian poet with a tragic but very eventful fate, was born.

Three days later he was baptized in the local church of the Kazan Icon of the Mother of God. Father and mother were of peasant origin, their marriage union from the very beginning was, to put it mildly, not very good, or rather, they were completely different people. Almost immediately after the wedding, Alexander Yesenin (the poet’s father) returned to Moscow, where he began working in a butcher shop. Sergei’s mother, in turn, not getting along with her husband’s relatives, returned to her father’s house, where Sergei spent the first years of his life. It was his maternal grandparents who pushed him to write his first poems, because after his father, his mother left the young poet and went to work in Ryazan. Yesenin’s grandfather was a well-read and educated man, he knew many church books, and his grandmother had extensive knowledge in the field of folklore, which had a beneficial effect on the early upbringing of the young man.

Sergei learned to read quite early - at the age of 5 years. At the age of 8-9 years he is already making attempts to write poetry, more like ditties.

Childhood and youth

Sergei Yesenin was born

October 3 (September 21, old style) 1895 in the village of Konstantinovo, Ryazan province, in the peasantry.

A peasant is a villager engaged in cultivating crops and breeding farm animals as his main job.

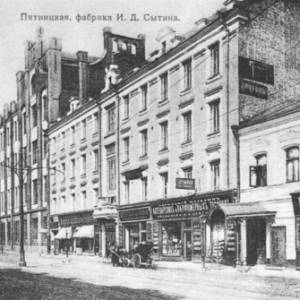

family, as a child he lived in his grandfather’s family. Among Yesenin’s first impressions were spiritual poems sung by wandering blind men and grandmother’s fairy tales. Having graduated with honors from the Konstantinovsky four-year school (1909), Seryozha Yesenin continued his studies at the Spas-Klepikovsky teacher’s school (1909-12), from which he graduated as a “teacher of the literacy school.” In the summer of 1912, Sergei moved to Moscow and for some time served in a butcher shop, where his father worked as a clerk. After a conflict with his father, he left the shop, worked in a book publishing house, then in the printing house of I. D. Sytin; during this period he joined the revolutionary-minded workers and found himself under police surveillance. At the same time, Yesenin studied at the historical and philosophical department of Shanyavsky University (1913-1915).

Literary debut. Success

Having composed poetry since childhood (mainly in imitation of A.V. Koltsov, I.S. Nikitin, S.D. Drozhzhin), Sergei Yesenin found like-minded people in the Surikov Literary and Musical Circle, of which he became a member in 1912. He began publishing in 1914 in Moscow children's magazines (his debut was the poem “Birch”).

In the spring of 1915, Sergei Yesenin came to Petrograd, where he met Alexander Blok, S. M. Gorodetsky, A. M. Remizov and others, and became close to N. A. Klyuev, who had a significant influence on him. Their joint performances with poems and ditties, stylized in a “peasant”, “folk” manner (Yesenin appeared to the public as a golden-haired young man in an embroidered shirt and morocco boots), were a great success.

"Radunitsa"

The first collection of poems by Sergei Yesenin - “Radunitsa” (1916) - was enthusiastically greeted by critics, who discovered a fresh spirit in it, noting the author’s youthful spontaneity and natural taste. In the poems of “Radunitsa” and subsequent collections (“Dove”, “Transfiguration”, “Rural Book of Hours”, all 1918, etc.) a special Yesenin “anthropomorphism” developed: animals, plants, natural phenomena, etc. are humanized by the poet, forming together with people connected by roots and all their being with nature, a harmonious, holistic and beautiful world.

At the intersection of Christian imagery, pagan symbolism and folklore stylistics, paintings of Yesenin’s Rus', colored by a subtle perception of nature, were born, where everything: a burning stove and a dog’s nook, an uncut hayfield and swamps, the hubbub of mowers and the snoring of a herd - became the object of the poet’s reverent, almost religious feeling (“ I pray at the red dawns, I take communion by the stream").

Revolution

At the beginning of 1918, Sergei Alexandrovich Yesenin moved to Moscow. Having greeted the revolution with enthusiasm, he wrote several short poems (“Dove of Jordan”, “Inonia”, “Heavenly Drummer”, all 1918, etc.), imbued with a joyful anticipation of the “transformation” of life. They combine godless sentiments with biblical imagery to indicate the scale and significance of the events taking place. Yesenin, glorifying the new reality and its heroes, tried to correspond to the times (“Cantata”, 1919). In later years, he wrote “Song of the Great March”, 1924, “Captain of the Earth”, 1925, etc.). Reflecting on “where the fate of events is taking us,” the poet turned to history (dramatic poem “Pugachev”, 1921).

Imagism

Searches in the field of imagery brought Sergei Aleksandrovich closer to A. B. Mariengof, V. G. Shershenevich, R. Ivnev, at the beginning of 1919 they united in a group of Imagists, Yesenin became a regular at the “Pegasus Stable” - a literary cafe of Imagists at the Nikitsky Gate in Moscow . However, the poet only partly shared their platform - the desire to cleanse the form of the “dust of content.” His aesthetic interests were turned to the patriarchal village way of life, folk art - the spiritual basis of the artistic image (treatise “The Keys of Mary”, 1919). Already in 1921, Sergei came out in print with criticism of the “buffoonish antics for the sake of antics” of his “brothers” Imagists. Gradually, elaborate metaphors disappeared from his lyrics.

"Moscow Tavern"

In the early 1920s, motifs of a “storm-ravaged life” (in 1920, his marriage to Z.N. Reich, which lasted about three years, broke up), drunken prowess, giving way to hysterical melancholy, appeared in Sergei Yesenin’s poems. The poet introduced himself as a hooligan, a brawler, a drunkard with a bloody soul, hobbling “from brothel to brothel,” where he was surrounded by “alien and laughing rabble” (collections “Confession of a Hooligan,” 1921, “Moscow Tavern,” 1924).

Isadora

An event in the life of Sergei Yesenin was a meeting with the American[en] dancer Isadora Duncan (autumn 1921), who six months later became his wife. On May 2, 1922, their wedding took place in the registry office of the Khamovnichesky district of Moscow. The newlyweds expressed a desire to bear the double surname Duncan-Yesenin. Leaving the registry office, Yesenin joyfully exclaimed: “Now I am Duncan.” Soon Duncan and Yesenin left for Leningrad, where Duncan gave a series of performances. They stayed in the best room at Angleterre.

A joint trip to Europe (Germany, Belgium, France, Italy) and America (May 1922 - August 1923), accompanied by noisy scandals and Yesenin’s shocking antics, revealed their “mutual misunderstanding,” aggravated by the literal lack of a common language (Yesenin did not speak foreign languages, Isadora learned several dozen Russian words). Upon returning to Russia they separated.

On August 14, 1923, Yesenin wrote “Iron Mirgorod”. In it, he shared his impressions of traveling to Europe and America: “...The world in which I lived before seemed terribly funny and absurd to me. I remembered about the “smoke of the fatherland”, about our village, where almost every peasant has a heifer sleeping on straw or a pig with piglets in his hut, he remembered our impassable roads after the German or Belgian highways and began to scold everyone who clings to “Rus” as if they were dirt and lice. From that moment on, I fell out of love with poor Russia..."

Yesenin's poems of the last years of his life

Sergei Yesenin returned to his homeland with joy, a feeling of renewal, and the desire “to be a singer and a citizen... in the great states of the USSR[en].” During this period (1923-1925) he created his best lines: the poems “The golden grove dissuaded...”, “Letter to mother”, “Now we are leaving little by little...”, the cycle “Persian motives”, the poem “Anna Snegina” and others .

The main place in Yesenin’s poems still belonged to the theme of the homeland, which now acquired dramatic shades. The once single harmonious world of Yesenin’s Rus' bifurcates: “Soviet Rus'” - “Leaving Rus'.” The motif of the competition between the old and the new, outlined in the poem “Sorokoust” (1920) (“a red-maned foal” and “a train on cast-iron paws”), has been developed in the poems of recent years: recording the signs of a new life, welcoming “stone and steel,” Sergei Yesenin all he felt more like a singer of a “golden log hut”, whose poetry “is no longer needed here” (collections “Soviet Rus'”, “Soviet Country”, both in 1925). The emotional dominant of the lyrics of this period were autumn landscapes, motives of summing up, and farewells.

Black man

On November 14, 1925, Yesenin wrote the poem “The Black Man.”

In November 1925, the editors of the New World magazine turned to Yesenin with a request to give him a new big thing. There were no new works, and the poet decided to publish “The Black Man.”

Yesenin first read “The Black Man” to his friends in the fall of 1923, shortly after returning to his homeland.

The poet worked on the poem for two evenings and on November 13. The manuscript was riddled with numerous corrections... Those who had previously heard the poem in his reading found that the final text was shorter and less tragic. Speaking about this thing, the poet more than once mentioned the influence of Pushkin’s “Mozart and Salieri”.

The poem “Black Man” was first published in the January issue of the magazine “New World”.

Tragic ending

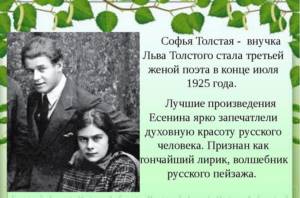

The last two years of Sergei Yesenin’s life were spent in constant travel: he traveled to the Caucasus three times, traveled to Leningrad several times, and to Konstantinovo seven times. Once again he tried to start a family life, but his union with S. A. Tolstoy (granddaughter of Leo Tolstoy) was not happy. At the end of November 1925, exhausted from wandering and bivouac life, the poet ended up in a psychoneurological clinic. One of his last works was the poem “The Black Man” (“My friend, my friend, I am very, very sick...”), in which the past life appears as part of a nightmare. Having interrupted the course of treatment, on December 23 Sergei Yesenin went to Leningrad, where on the night of December 28, in a state of deep mental depression at the Angleterre Hotel, he committed suicide.

Postscriptum

A specially created commission in 1993 did not confirm widespread versions about other circumstances of the poet’s death. (M.K. Evseeva)

Sergei Yesenin about himself:

I was born in 1895, September 21, in the Ryazan province, Ryazan district, Kuzminsk volost, in the village of Konstantinov.

From the age of two I was raised by a rather wealthy maternal grandfather, who had three adult unmarried sons, with whom I spent almost my entire childhood. My uncles were mischievous and desperate guys. When I was three and a half years old, they put me on a horse without a saddle and immediately started galloping. I remember that I went crazy and held my withers very tightly. Then I was taught to swim. One uncle (Uncle Sasha) took me into a boat, drove away from the shore, took off my underwear and threw me into the water like a puppy. I flapped my hands ineptly and frightenedly, and until I choked, he kept shouting: “Eh! Bitch! Well, how good are you?...” “Bitch” was a term of endearment.

After about eight years, I often replaced another uncle’s hunting dog and swam around the lakes after shot ducks. He was very good at climbing trees. Among the boys he was always a horse breeder and a big fighter and always walked around with scratches. Only my grandmother scolded me for my mischief, and my grandfather sometimes encouraged me to fight with my fists and often said to my grandmother: “You’re a fool, don’t touch him, he’ll be stronger that way!” Grandmother loved me with all her might, and her tenderness knew no bounds.

On Saturdays they washed me, cut my nails and crimped my hair with cooking oil, because not a single comb could handle curly hair. But the oil didn’t help much either. I’ve always yelled obscenities, and even now I have some kind of unpleasant feeling about Saturday.”

“From the age of eight, my grandmother dragged me to different monasteries; because of her, all sorts of wanderers and pilgrims were always living with us. Various spiritual poems were chanted. Grandfather is opposite. He was not a fool to drink. On his part, eternal unmarried weddings were arranged.

...As for the rest of the autobiographical information, they are in my poems.” (October 1925, Sergei Yesenin" Yesenin S. About myself - In the book. Yesenin S. Poems. Poems. - Kazan, 1975, p. 4.)

Education

In September 1904, Sergei entered the Konstantinovsky Zemstvo School, where he studied for 5 years, although his studies were supposed to last a year less.

This was due to the bad behavior of young Seryozha in the third grade. During his studies, he and his mother return to his father's house. Upon graduation, the future poet receives a certificate of merit. In the same year, he successfully passed the exams for admission to the parish teacher's school in the village of Spas-Klepiki in his native province. During his studies, Sergei settled there, coming to Konstantinovskoye only during the holidays. It was at the training school for rural teachers that Sergei Alexandrovich began to regularly write poetry. The first works date back to early December 1910. Within a week the following appear: “The Coming of Spring”, “Autumn”, “Winter”, “To Friends”. By the end of the year, Yesenin manages to write a whole series of poems.

In 1912 he graduated from school and received a diploma as a school literacy teacher.

Moving to Moscow

After graduating from school, Sergei Alexandrovich leaves his native land and moves to Moscow. There he gets a job in Krylov's butcher shop. He begins to live in the same house where his father lived, on Bolshoy Strochenovsky Lane, now the Yesenin Museum is located here. At first, Yesenin’s father was happy about his son’s arrival, sincerely hoping that he would become a support for him and would help him in everything, but after working in the shop for some time, Sergei told his father that he wanted to become a poet and began to look for a job he liked.

At first, he distributed the social democratic magazine “Ogni”, with the intention of being published in it, but these plans were not destined to come true, since the magazine was soon closed.

Afterwards, he gets a job as an assistant proofreader in the printing house of I.D. Sytin. It was here that Yesenin met Anna Izryadnova, who would later become his first common-law wife. At the same time, he entered the Moscow City People's University as a student. Shanyavsky for a historical and philological cycle, but immediately abandons him. Working in the printing house allowed the young poet to read many books and gave him the opportunity to become a member of the Surikov literary and musical circle. The poet’s first common-law wife, Anna Izryadnova, describes Yesenin in those years:

He was reputed to be a leader, attended meetings, distributed illegal literature. I pounced on books, read all my free time, spent all my salary on books, magazines, did not think at all about how to live...

Brief information

Quick answers to popular questions:

- Full name, surname, patronymic: Sergey Aleksandrovich Yesenin;

- Nickname: Atheist;

- Date of birth: October 3, 1895;

- Date of death: December 28, 1925;

- Yesenin lived: 30 years;

- Homeland: Russia;

- Citizenship: Russia;

- Nationality Russian;

- Age: Silver Age;

- Libra;

- Height: 1.68 cm;

- Weight: 78 kg;

- Eye color: blue.

Interesting to know: Sergei Yesenin - the personal life of the poet. We suggest you read: Sergei Yesenin - personality characteristics. Article on the topic: Sergei Yesenin - 21 most interesting facts.

S. Yesenin a writer or a poet?

Sergei Yesenin was a poet!

When did Yesenin start writing?

Sergei began to engage in creativity at the age of 9.

What did S. Yesenin write about?

The poet lived by the revolution and its greatness. Sergei Alexandrovich lived for the future and was very eager for something new. In his work there is a lot about the goals of the revolution, about the future, about socialism.

What did S. Yesenin do?

Sergei Alexandrovich worked in a butcher shop, book publishing, and then in a printing house.

What made S. Yesenin famous?

The Russian poet became famous for his original style and interesting style.

The flourishing of the poet's career

At the beginning of the 14th year, Yesenin’s first known material was published in the Mirok magazine.

The verse “Birch” was published. In February, the magazine publishes a number of his poems. In May of the same year, the Bolshevik newspaper “The Path of Truth” began publishing Yesenin. In September, the poet again changed his job, this time becoming a proofreader at the Chernyshev and Kobelkov trading house. In October, the magazine “Protalinka” published the poem “Mother’s Prayer,” dedicated to the First World War. At the end of the year, Yesenin and Izryadnova gave birth to their first and only child, Yuri.

Unfortunately, his life would end quite early; in 1937, Yuri would be shot, and, as it later turned out, on false charges brought against him.

After the birth of his son, Sergei Alexandrovich leaves his job at the trading house.

At the beginning of the 15th year, Yesenin continued to actively publish in the magazines “Friend of the People”, “Mirok”, etc. He worked for free as a secretary in a literary and musical circle, after which he became a member of the editorial commission, but left it due to disagreements with other members of the commission on the selection of materials for the magazine “Friend of the People”. In February, his first well-known article on literary topics, “The Yaroslavs are Crying,” was published in the magazine “Women’s Life.”

In March of the same year, during a trip to Petrograd, Yesenin met Alexander Blok, to whom he read his poems in his apartment. Afterwards, he actively introduced his work to many famous and respected people of that time, simultaneously establishing profitable acquaintances with them, among them A.A. Dobrovolsky, V.A. Rozhdestvensky. Sologub F.K. and many others. As a result, Yesenin’s poems were published in a number of magazines, which contributed to the growth of his popularity.

In 1916, Sergei entered military service and in the same year published a collection of poems “Radunitsa”, which made him famous. The poet began to be invited to perform before the Empress in Tsarskoye Selo. At one of these speeches, she gives him a gold watch with a chain, on which the state emblem was depicted.

Yesenin

ESENIN Sergei Alexandrovich [21.9 (3.10).1895, p. Konstantinovo Ryazan district. Ryazan province. – 12/28/1925, Leningrad; buried in Moscow], Russian. poet. Born into the family of a peasant woman and a clerk. He began writing poetry at a second-grade teacher's school in Spas-Klepiki, where he entered after graduating from a four-year school in Konstantinov in September. 1909. The first poetic. the experiments were colored by the influence of S. Ya. Nadson. From the end of July 1912 to March 1915 he lived in Moscow, where from September. 1913 and before 1915 was a student of history and philosophy. academic cycle Moscow branch mountains People's University named after A. L. Shanyavsky. Having tried many styles. manners, towards the end of Moscow. period acquired its own. poetic style, combining folk “peasant” imagery in the spirit of A.V. Koltsov with the achievements of Russian. symbolism (primarily A. A. Blok). Also experienced means. the influence of A. A. Fet, noticeable in the first published verse. “Birch” (in the January issue of the Moscow children's magazine “Mirok” for 1914, under the pseudonym Ariston).

At the beginning of March 1915 E. arrived in Petrograd. Communication with Blok, S. M. Gorodetsky, Z. N. Gippius, D. S. Merezhkovsky, D. V. Filosofov convinced E. of the need to enrich his religious lyrics. motives in demand by Russians. modernism. In the verses of his 1st book. “Radunitsa” (1916) is dominated by a kind of pantheism (parallels between nature and the temple are elegantly and unobtrusively introduced into the text), the style is distinguished by sparingly selected dialecticisms. An important milestone in poetry. E.'s biography was his correspondence, and then his meeting (in October 1915) with N. A. Klyuev, who took on the role of teacher and guardian of the young poet: in 1915–17 his influence was manifested both in poetry and in the appearance of E. ., stylized as the fabulous Ivan Tsarevich.

Feb. and Oct. E. received the revolution of 1917 with enthusiasm. In the infamous poem “Transfiguration” (December 1917), he, having sharply changed his manner, voluntarily or unwittingly translated the slogans of the International into the language of Old Testament legends. About changing your worldview. E.’s priorities were loudly stated in the poem “Inonia” (1918) with its key image of the rejected Communion. In 1917–18, E. was closely associated with the “Scythians” group of R.V. Ivanov-Razumnik, ch. poetic Andrei Bely became an authority for E. Poetic E.'s achievements of this time were reflected not so much by his 2nd book. “Dove”, published in Petrograd (1918), which included poems from 1916–17, as well as a series of Moscow. collections published in 1918–20 (“Transfiguration”, “Rural Book of Hours”, 2nd edition of “Radunitsa”, all 1918, etc.).

In the end 1918 – beginning 1919 E., together with A. B. Mariengof, V. G. Shershenevich and others, created a group of imagists (see Imagism). Not only the tactics of winning high-profile pop success with the help of scandals, but also the very poetics of imagism were inherited by the Russians. futurism. Synthesis of pop, designed for the indispensable utterance of a word, spectacular futuristic. metaphors with “bottomless soiliness” (according to the formula of B. L. Pasternak) provided E. with unprecedented success among readers, especially among a very large number. layers of yesterday's immigrants from the village. Most means. The achievements of E.’s imagist period were his poem “Sorokoust” (1920), a book of poems “Confession of a Hooligan,” as well as a dramatic work. poem “Pugachev” (both 1921). The most famous literary criticism is maintained in the spirit of the ideas of imagism. E.’s work is a poetological treatise “The Keys of Mary” (1919).

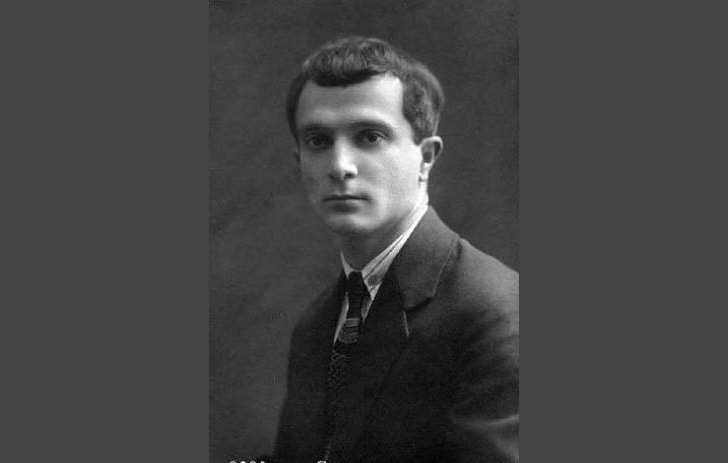

S. A. Yesenin. Photograph.1923.

S. A. Yesenin. Portrait by N. I. Altman. 1926.

In Oct. 1921 E. met Amer. dancer A. Duncan; On May 2, 1922, they officially registered their marriage (from July 1917 to October 1921, E. was married to Z. N. Reich; from September 1925, to S. A. Tolstoy). E. made trips with Duncan across Europe and America (May 1922 - Aug. 1923), not least in the hope of world fame. The disappointment that befell the poet in these aspirations was reflected in his essay about America, “Iron Mirgorod,” published shortly after his return to Russia (1923). In the last years of his life, E. was inclined towards an alliance with the Sov. power, problematized by longing for the “vanishing Rus'.” In the works of this period, there is a noticeable tendency to reproduce and rethink the key images of A. S. Pushkin’s poetry. In E.'s later lyrics, the collection stands out. "Persian Motifs" (1925). The final result for E. was the poem “The Black Man” (1925), which played on Pushkin’s themes - an uncompromising author’s confession, the poet’s confession that all his life he wore precisely calculated masks. This state of mental discord, coupled with a persecution mania, pushed E. to commit suicide (not a single version of his murder is based on serious factual grounds).

Zinaida Reich

In 1917, while in the editorial office of “The Cause of the People,” Yesenin met the assistant secretary, Zinaida Reich, a woman of very good intelligence who spoke several languages and typewriting.

The love between them did not arise at first sight. It all started with walks around Petrograd with their mutual friend Alexei Ganin. Initially, they were competitors and at some point the comrade was even considered a favorite, until Yesenin confessed his love to Zinaida, after hesitating briefly, she reciprocated, and it was immediately decided to get married. At that moment, young people were experiencing serious financial problems. They solved the money problem with the help of Reich's parents, sending them a telegram asking them to send them funds for the wedding. The money was received without any questions asked. The newlyweds got married in a small church, Yesenin picked wildflowers and made a wedding bouquet from them. Their friend Ganin acted as a witness.

However, from the very beginning, their marriage went wrong; on their wedding night, Yesenin learns that his beloved wife was not innocent, and had already shared a bed with someone before him. This really touched the poet's heartstrings. At that moment, Sergei’s blood began to leap, and deep resentment settled in his heart. After returning to Petrograd, they began to live separately, and only two weeks later, after a trip to her parents, they began to live together.

Perhaps, playing it safe, Yesenin forces his wife to leave her job from the editorial office, and like any woman of that time, she had to obey, fortunately by that time the family’s financial situation had improved, because Sergei Alexandrovich had already become a famous poet with good fees. And Zinaida decided to get a job as a typist at the People's Commissariat.

For some time, a family idyll was established between the spouses. There were many guests in their house, Sergei organized receptions for them, and he really liked the role of a respectable host. But it was at this moment that problems began to appear that greatly changed the poet. He was overcome by jealousy, and problems with alcohol were added to this. Once, having discovered a gift from an unknown admirer, he caused a scandal, while obscenely insulting Zinaida; later they reconciled, but they could not return to their previous relationship. Their quarrels began to occur more and more often, with mutual insults.

After the family moved to Moscow, the problems did not go away, but rather intensified; the comfort of home, the friends who supported them, were gone, and instead were the four walls of a run-down hotel room. Added to all this was a quarrel with his wife over the birth of children, after which she decided to leave the capital and go to Oryol to live with her parents. Yesenin drowned out the bitterness of parting with alcohol.

In the summer of 1918, their daughter was born, who was named Tatyana. But the birth of a child did not help strengthen the relationship between Yesenin and Reich. Due to rare meetings, the girl did not become attached to her father at all, and in this he saw the “machinations” of the mother. Sergei Alexandrovich himself believed that his marriage had already ended then, but officially it lasted for several more years. In 1919, the poet made attempts to renew the relationship and even sent money to Zinaida.

Reich decided to return to the capital, but the relationship again did not go well. Then Zinaida decided to take everything into her own hands and, without her husband’s consent, give birth to a second child. This became a fatal mistake. In February 1920, their son is born, but the poet is not present at the birth or after it. The boy’s name is chosen during a telephone conversation and they settle on Konstantin. Yesenin met his son on the train when he and Reich accidentally crossed paths in one of the cities. In 1921, their marriage was officially dissolved.

Imagism

In 1918, Yesenin met Anatoly Mariengof, one of the founders of imagism.

Over time, the poet will join this movement. During the period of his passion for this direction, he wrote a number of collections, including “Treryadnitsa”, “Poems of a Brawler”, “Confession of a Hooligan”, “Moscow Tavern”, as well as the poem “Pugachev”. Yesenin significantly helped the formation of imagism in the literature of the Silver Age. Due to his participation in Imagist actions, he was arrested. At the same time, he had a conflict with Lunacharsky, who was dissatisfied with his work.

Isadora Duncan

Two days before receiving an official divorce from Zinaida Reich, at one of the evenings in the house of the artist Yakulov, Yesenin met the famous dancer Isadora Duncan, who came to open her dance school in our country.

She did not know Russian, her vocabulary consisted of only a couple of dozen words, but this did not stop the poet from falling in love with the dancer at first sight and receiving a passionate kiss from her that same day. By the way, Duncan was 18 years older than her beau. But neither the language barrier nor the age difference prevented Yesenin from moving to the mansion on Prechistenka, where the dancer lived.

Soon Duncan was no longer satisfied with the way her career was developing in the Soviet Union, and she decided to return back to her homeland - the United States. Isadora wanted Sergei to follow her, but bureaucratic procedures prevented this. Yesenin had problems obtaining a visa, and in order to get it, they decided to get married.

The wedding process itself took place in the Khamovnichesky registry office in Moscow. On the eve of this, Isadora asked to correct the year of her birth so as not to embarrass her future husband, he agreed.

The wedding ceremony took place on May 2, in the same month the couple left the Soviet Union and went on the Yesenina-Duncan tour (both spouses took this surname) first to Western Europe, after which they were supposed to go to the USA.

The newlyweds' relationship did not work out from the very beginning of the trip. Yesenin was accustomed to special treatment in Russia and to his popularity; he was immediately perceived as the wife of the great dancer Duncan.

In Europe, the poet again has problems with alcohol and jealousy. Having gotten pretty drunk, Sergei began to insult his wife, roughly grabbing her, sometimes beating her. Once Isadora even had to call the police to calm down the raging Yesenin. Each time after quarrels and beatings, Duncan forgave Yesenin, but this not only did not cool his ardor, but, on the contrary, warmed him up. The poet began to speak contemptuously about his wife among his friends.

In August 1923, Yesenin and his wife returned to Moscow, but even here their relationship did not go well. And already in October he sends Duncan a telegram about the final severance of their relationship.

Last years and death

After breaking up with Isadora Duncan, Yesenin’s life slowly went downhill.

Regular consumption of alcohol, nervous breakdowns caused by public persecution of the poet in the press, constant arrests and interrogations, all this greatly undermined the poet’s health. In November 1925, he was even admitted to the Moscow State University clinic for patients with nervous disorders. Over the last 5 years of his life, 13 criminal cases were opened against Sergei Yesenin, some of which were fabricated, for example, charges of anti-Semitism, and the other part were related to alcohol-related hooliganism.

Yesenin’s work during this period of his life became more philosophical; he rethought many things. The poems of this time are filled with musicality and light. The death of his friend Alexander Shiryaevets in 1924 pushes him to see the good in simple things. Such changes help the poet resolve the intrapersonal conflict.

Personal life was also far from ideal. After breaking up with Duncan, Yesenin moved in with Galina Benislavskaya, who had feelings for the poet. Galina loved Sergei very much, but he did not appreciate it, he constantly drank and made scenes. Benislavskaya forgave everything, was by his side every day, pulled him out of various taverns, where his drinking buddies got the poet drunk at his own expense. But this union did not last long. Having left for the Caucasus, Yesenin marries Tolstoy’s granddaughter, Sophia. Having learned this, Benislavskaya goes to the physio-dietetic sanatorium named after. Semashko with a nervous disorder. Subsequently, after the death of the poet, she committed suicide at his grave. In her suicide note, she wrote that Yesenin’s grave contained all the most precious things in her life.

In March 1925, Yesenin met Sofia Tolstoy (granddaughter of Leo Tolstoy) at one of the evenings in the house of Galina Benislavskaya, where many poets gathered. Sophia came with Boris Pilnyak and stayed there until late in the evening. Yesenin volunteered to accompany her, but instead they walked for a long time around Moscow at night. Afterwards, Sophia admitted that this meeting decided her fate and gave her the greatest love of her life. She fell in love with him at first sight.

After this walk, Yesenin often began to appear at the Tolstoys’ house, and already in June 1925 he moved to Pomerantsevy Lane to live with Sophia. One day, while walking along one of the boulevards, they met a gypsy woman with a parrot, who told them a wedding, and during the fortune-telling the parrot took out a copper ring, Yesenin immediately gave it to Sophia. She was incredibly happy with this ring and wore it for the rest of her life.

On September 18, 1925, Sergei Alexandrovich entered into his last marriage, which would not last long. Sophia was as happy as a little girl, Yesenin was also happy, boasting that he had married the granddaughter of Leo Tolstoy. But Sofia Andreevna’s relatives were not very happy with her choice. Immediately after the wedding, the poet’s constant binges, leaving home, drinking sprees and hospitals continued, but Sophia fought for her beloved until the last.

In the autumn of the same year, a long binge ended with Yesenin’s hospitalization in a psychiatric hospital, where he spent a month. After his release, Tolstaya wrote to her relatives so that they would not judge him, because no matter what, she loved him, and he made her happy.

After leaving the psychiatric hospital, Sergei leaves Moscow for Leningrad, where he checks into the Angleterre Hotel. He meets with a number of writers, including Klyuev, Ustinov, Pribludny and others. And on the night of December 27-28, according to the official version of the investigation, he takes his own life by hanging himself from a central heating pipe with a rope. His suicide note read: "Goodbye, my friend, goodbye."

Investigative authorities refused to initiate a criminal case, citing the poet’s depressive state. However, many experts, both of that time and contemporaries, are inclined to the version of Yesenin’s violent death. These doubts arose due to an incorrectly drawn up report on the inspection of the suicide site. Independent experts found traces of violent death on the body: scratches and cuts that were not taken into account.

When analyzing documents from those years, other inconsistencies were discovered, for example, that you cannot hang yourself from a vertical pipe. A commission created in 1989, after conducting a serious investigation, came to the conclusion that the poet’s death was natural - from strangulation, refuting all the speculation that was very popular in the 70s in the Soviet Union.

After the autopsy, Yesenin’s body was transported by train from Leningrad to Moscow, where on December 31, 1925 the poet was buried at the Vagankovsky cemetery. At the time of his death he was only 30 years old. They said goodbye to Yesenin at the Moscow Press House; thousands of people came there, even despite the December frosts. The grave is still there today, and anyone can visit it.

Life story of Sergei Yesenin (32 photos)

Author: anthrax

03 October 2021 13:02

Community: Stars and celebrities: stories, photos, sensations

Tags: USSR Yesenin history facts

13775

32

On October 3, 1895, in the village of Konstantinov, Ryazan province, the future great poet Sergei Yesenin was born into a peasant family.

0

See all photos in the gallery

0

In January 1924, the poet Sergei Yesenin was discharged from a sanatorium for nervous patients, releasing him to say goodbye to the deceased leader of the revolution, Vladimir Ilyich Lenin. Shortly before Yesenin’s discharge, the poet Rurik Ivnev visited Yesenin, who described his comrade’s painful condition this way: “He spoke in a half-whisper, looked around, then began to get nervous, said that he needed to move away from the window, because they were watching him, they would see him and throw a stone at him.” Memoirs of friends and contemporaries of that period describe a disorder that in psychiatry is called delusions of persecution.

0

The personality of the great Russian poet Sergei Aleksandrovich Yesenin is complex and multifaceted, and memories of him are contradictory, but researchers and admirers of the poet’s work agree that he was extremely talented and loved Russia to the point of oblivion.

0

Be that as it may, the magnificent creative legacy that Sergei Yesenin left includes not only poems about the beauties of Russian nature, well known to us from the school curriculum, but also dramatic cycles telling about the mental torment of the poet, who suffered, according to experts, severe alcohol dependence. The consequences of alcohol abuse were attacks of melancholy and unmotivated aggression, delusions of persecution with visual and auditory hallucinations, painful insomnia, severe remorse and suicidal thoughts.

0

Already in adolescence, Yesenin began to manifest seemingly unjustified short temper, anger and conflict. The future poet did not tolerate contradictions and superiority over himself, no matter how it was expressed. Anger, according to the recollections of Yesenin’s sisters, flared up in him suddenly and disappeared just as suddenly. He assessed people by their attitude towards each other and divided them into good and evil, selfless and greedy, truthful and deceitful.

0

Yesenin made his first suicide attempt, which we learn about from the poet’s letter sent to his school friend Grisha Panfilov, at the age of 17: “I couldn’t stand the fact that empty tongues were chattering about me, and drank some essence. I lost my breath and for some reason began to foam. I was conscious, but everything in front of me was obscured by some kind of cloudy haze.” Yesenin took this decisive step some time after he moved out from his father in the hope of making his way into a literary future without outside help, but a collision with harsh reality, life from hand to mouth and the need to take care of his daily bread led the young man to despair. (In the photo: Grigory Panfilov - left and Sergei Yesenin - right.)

0

Finally, in March 1913, Yesenin found work in the Moscow printing house of I.D. Sytin on Pyatnitskaya Street, but the money he earns is only enough to feed himself and buy books, and his life continues to remain unsettled. The young man's restless character and anger did not contribute to his rapprochement with the printing house workers. He shares his thoughts only with his friend Grisha Panfilov: “How ridiculous our life is. She distorts us from the cradle and instead of true people some freaks come out. Here they consider me crazy, and they were about to take me to a psychiatrist, but I sent everyone to Satan and live, although some are afraid of my approach. Yes, Grisha, love and have pity on people. Love the oppressors and do not stigmatize them.”

0

The motive of his own early death is often heard in the poet’s poems written in different years. “I meet everything, I accept everything, I’m glad and happy to take out my soul. I came to this earth to quickly leave it” (1914). “I see myself deceased in a coffin under the hallelujah lamentations of the sexton, I lower my dead eyelids lower, placing two copper spots on them...” (1924).

0

Sergei Yesenin met the American dancer Isadora Duncan in 1921. Isadora was 17 years older than the poet, she doted on her young lover, wrote “I love Yesenin” on the mirror with lipstick, gave him expensive gifts and could not refuse him anything.

0

Isadora Duncan’s affection for Sergei Yesenin is often explained by the poet’s resemblance to the son of a dancer who tragically died in childhood. Yesenin and Duncan got married in May 1922, then Isadora was going on a tour abroad, and Sergei would not have been given a visa if he had not been married to her. On May 10, 1922, the couple flew from Moscow to Kaliningrad, and from there to Berlin.

0

Soon after arriving in Germany, Isadora Duncan began touring around the country, on which she was accompanied by Sergei Yesenin, who had now lost the opportunity to devote all his time to writing poetry. The constant internal struggle between the desire for creative work and the limited ability to do this undermined his nervous system and caused mental suffering. He tried to fill the resulting void with expensive suits and shoes, which Duncan sewed with his money, and poured alcohol on him.

0

One of the doctors drew Isadora Duncan’s attention to the poet’s unhealthy appearance: a pale face, bags under the eyes, puffiness, cough, hoarse voice - and warned that he needed to immediately stop drinking alcohol, which even in small doses has a detrimental effect, “otherwise you will suffer.” there will be a maniac in our care.” Drunk Yesenin was prone to attacks of unmotivated aggression, primarily against Isadora, but he often got it on those around him.

0

No matter how hard Isadora Duncan tried to convince the reading public in Europe and America that Sergei Yesenin was a brilliant Russian poet, he was perceived only as the young wife of a famous dancer, they admired his elegance and physical form, and predicted a sports career. “I pray to God not to die in soul and not to lose love for my art. Nobody needs it here,” Yesenin wrote to his friend Anatoly Mariengof.

0

After a long stay abroad, Sergei Yesenin and Isadora Duncan returned to Moscow and soon separated. When meeting with her translator Ilya Shneider, Isadora said: “I took this child from Russia, where living conditions were difficult. I wanted to save it for the world. Now he has returned to his homeland to save his mind, since he cannot live without Russia.”

0

Living in Moscow, Yesenin wrote poetry almost every day, but this did not stop him from meeting his former friends, who spent a lot of time in restaurants, where they drank and ate at Sergei Alexandrovich’s expense. The poet Vsevolod Rozhdestvensky recalled how Yesenin changed after returning to Russia: “The face is swollen, the eyes are dull and sad, heavy eyelids and two deep folds near the mouth. The expression of deep weariness did not leave him, even when he laughed. My hands were shaking noticeably. Everything about him testified to some kind of internal confusion.” At the same time, Rozhdestvensky drew attention to how quickly Sergei Yesenin moved from explosions of joy to the darkest melancholy, how unusually closed and distrustful he was.

0

The poet increasingly found himself in scandalous stories, became the initiator of fights, and insulted others. After one of these scandals, Yesenin was sent to a sanatorium for nervous patients, from where he was discharged in January 1924 to say goodbye to the deceased leader of the revolution, Vladimir Ilyich Lenin.

0

After his discharge, rumors began to circulate in Moscow about the poet’s eccentricities; perhaps they were somewhat exaggerated by the press. As if in one cafe he wanted to hit someone with a chair, attacked the doorman, whose behavior seemed suspicious, and in another place “threw a plate of vinaigrette at a visitor.” However, people close to Sergei Yesenin unanimously began to say that the poet was suffering from a mental disorder.

0

Memoirs of friends and contemporaries of that period describe a disorder that in psychiatry is called delusions of persecution. From the memoirs of Ilya Erenburg: “Yesenin could not find a place for himself anywhere, he suspected even his friends of intrigues, and believed that he would soon die.” The editor of the Krasnaya Nov magazine, Alexander Voronsky, wrote: “Yesenin said that he has many enemies who are conspiring against him and are going to kill him.” One day, sitting in Voronsky’s office, the poet became worried, “opened the door and, seeing the guard on duty, began to strangle him,” mistaking him for a murderer. Voronsky was sure that at that moment Sergei Yesenin was hallucinating.

0

Yesenin told his friends that he was once attacked by bats in a hotel: “The gray cemetery freaks kept me awake all night.” According to him, “they flew into the window: first one hung on the bed, I hit him with my hand, and he sat on the closet. When I turned on the light, I saw that his claws were red, as if manicured, and his mouth was a blood-red stripe.”

0

In March 1925, Sergei Yesenin met Sofia Andreevna Tolstoy, the granddaughter of Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy. Sofya Andreevna was delighted with Yesenin’s courtship, she was ready to become an assistant and friend for him, which she declared to her relatives, who reacted negatively to her choice, knowing about the groom’s penchant for abusing alcohol and his restless character. Friends noticed that Yesenin had changed with Tolstoy; he was often seen walking around Moscow on her arm, always sober, in an elegant suit. It seemed to those around him that a strong and fruitful life would begin for him, but this was not destined to happen. In September 1925, Sergei Yesenin married Sofya Tolstoy and moved into her apartment. The poet told his friends that the bulky furniture in his apartment irritated him and that he was “overcome by his beard,” i.e. portraits of Leo Tolstoy on the walls and tables, at which Yesenin tried to throw something heavy. He began inviting friends to his apartment, having drinking bouts, or going to see them and invariably returning drunk.

0

One day Yesenin threw his bust by the sculptor Konenkov from the balcony of the Tolstoys’ apartment, declaring that “Seryozha is hot and stuffy.” The bust fell into pieces. Sofia Tolstoy’s mother later told her friend: “Some types lived with us, they were hooligans and drunkards, they slept in our beds. They ate and drank with Yesenin’s money, but Sonya had no shoes. But you can't blame him. He is a sick man. I feel sorry for Sonya."

0

In November 1925, Yesenin went to Leningrad to visit friends and stayed with the writer Sakharov. From Sakharov’s memoirs it is known that at night he felt that someone was strangling him, turned on the light and saw Yesenin, he looked scared. Sakharov managed to calm the poet down and put him to bed, but in the morning there was the sound of broken glass. Sakharov saw Yesenin standing in the middle of the room in tears, covered in shrapnel. The writer realized that Sergei had suffered another attack of illness, sent him to Moscow and advised his family to show him to the doctors.

0

On November 26, 1925, Sergei Yesenin was hospitalized at the Psychiatric Clinic of Moscow University, which at that time was headed by Professor Pyotr Borisovich Gannushkin, well-known in the medical world.

0

At the clinic, Yesenin was allocated a separate room on the second floor. The atmosphere here was comfortable, close to home, there were carpets and carpet runners everywhere, soft sofas and armchairs, and paintings hanging on the walls. While in a psychiatric hospital, Sergei Yesenin did not stop writing poetry. On the third day of his stay in the clinic, from the window he saw a maple covered with snow, on the same day a famous poem was born: “You are my fallen maple, you are an icy maple, why are you standing bent over under the white blizzard?”

0

Despite the seemingly comfortable living conditions, Yesenin was irritated by everything: the constantly open door of the hospital room, into which curious patients looked, and the light of a night lamp that never turned off, and walks accompanied by staff (the poet was under constant supervision for the reason suicidal thoughts).

0

On December 20, 1925, Yesenin was visited in the hospital by Anna Abramovna Berzin, who later wrote in her memoirs about this visit: “The poet’s attending physician - a kind and gentle person - warned me not to give Yesenin piercing, cutting objects, as well as ropes and laces, so that the patient cannot use them for suicidal purposes. He explained that the illness was serious and there was no hope of recovery and that he would live no more than a year.”

0

Yesenin refused to meet with his wife Sofia Andreevna, considering her to be the initiator of his placement in the clinic. And on December 21, 1925, the poet was not found in the ward. After a meeting with some friends who brought with them a winter coat, hat and shoes, Yesenin changed clothes and, under the guise of a visitor, walked past the guards. The clinic took measures to search for the fugitive, they searched everywhere, the attending physician Aranson called the poet’s relatives and friends, and went home to those who did not have a telephone. Three days after escaping from the hospital, Yesenin showed up at the Tolstoys’ apartment, the family breathed a sigh of relief, but the joy was short-lived. Without saying hello, without saying a word, the poet began feverishly packing his things, and when the suitcases were ready, he went out without saying goodbye and slammed the door. From Moscow, Sergei Yesenin fled to Leningrad, where he arrived on December 24, 1925.

0

Upon arrival in Leningrad, the poet rented a room on the second floor of the Angleterre Hotel. In the evening, some literary acquaintances visited him and reminisced about the past. Yesenin read the poem “The Black Man” in its finished form: “My friend, my friend, I am very, very sick, I don’t know where this pain came from, either the wind whistles over an empty and deserted field, or like a grove in September , showers your brain with alcohol..."

0

The next day, December 25, Sergei Yesenin asked the poet Erlich to stay overnight with him, as is known from the latter’s memoirs. Ehrlich wrote that Yesenin experienced fears, was afraid to remain alone in the room, explained that they wanted to kill him, and warned the guard on duty that no one would be allowed to see him without permission. (In the photo - Wolf Ehrlich.)

0

From the investigation documents it is known that on December 27 Yesenin again had many guests. The poet treated everyone to wine and read “The Black Man” again, then tore the scribbled sheet out of the notebook and put it in the poet Erlich’s inner pocket, telling him to read it later. Yesenin explained that he wrote this poem in blood this morning, “since there is not even ink in this lousy hotel,” and showed the cuts on his hand from which he took the blood. Erlich did not imagine that he would see Yesenin alive for the last time.

0

Yesenin's body was discovered on December 28, 1925. From the testimony of the commandant of the Angleterre Hotel Nazarov: “...citizen Ustinova and with her citizen Erlich caught up with me and, clutching my head, in horror asked me to return to room 5. I entered and saw Yesenin hanging on a rope from a steam heating pipe.” (Photograph of room No. 5, taken after the discovery of the poet’s body.)

0

Sergei Yesenin was buried on December 31, 1925 in Moscow at the Vagankovskoye cemetery.

Source:

More cool stories!

- Red film, fantastic story

- Cartoon "Bremen Town Musicians" - a masterpiece without awards

- Five interesting facts about everything in the world

- A girl from Novosibirsk went fishing with a bear

- People clearly did not expect such mean things from nature!

subscribe to the community “Stars and Celebrities: Stories, Photos, Sensations”

Tags: USSR Yesenin history facts

Do you like to remember how things were before? Join us, let's feel nostalgic together:

117 1 116

Liked

116 3

38

Partner news